Clean Water Mantra: Slow It, Spread It, Sink It

To make sure we have enough clean water for drinking and irrigation, and to keep the force of water from eroding the landscape, permaculture has a simple mantra: “Slow it, spread it, sink it.”

Water is essential for all life on earth. Although it covers 71 percent of the earth’s surface, there is a limited supply of fresh water, which exists primarily in the ground (groundwater), but also in streams and lakes. Only 3 percent of water on the planet is freshwater, and a mere 0.03 percent is not in glaciers or deep groundwater. Whether you live in the drought-stricken West or in a region that experiences unpredictable rainfall, you know what a precious resource fresh, clean water is.

Threats to our limited freshwater are largely from overuse and pollution. Groundwater levels are dropping; many water bodies are contaminated with nutrients, sediment, or toxic compounds. The future of our water supply is uncertain, and planning for our clean water needs should be a top priority. The ethics of permaculture — care for the earth and care for people — indicate that we should use water thoughtfully and leave the water cleaner than when it arrives to us. The ethic of fair share asks us to limit our consumption, in order to leave enough clean water for others. There are many ways to use less water, keep it clean, and collect the water we need for our personal and community uses.

In most towns, cities, and developments, water is moved off the land as quickly as possible. Although it’s critical to control flooding, when water is quickly funneled into rivers and streams without first infiltrating the ground, it can cause rivers to rise quickly and flood downstream areas, decrease groundwater levels, and begin a cycle of stream channel erosion.

To make sure we have enough clean water for drinking and irrigation, and to keep the force of water from eroding the landscape, permaculture has a simple mantra: “Slow it, spread it, sink it” — that is, catch the water, hold it on-site, and get the water back into the ground. In the process of catching and distributing the water, we hold it in catchments like ponds, tanks, cisterns, and swales and use it (for growing food, irrigation, drinking, and so on) before it infiltrates the ground. There are a few ways to do this.

STORE WATER IN SOIL. Soil is by far the largest reservoir of water on the landscape, and given the choices of water storage, increasing the soil’s water-holding capacity is the cheapest option. Soil that is deep, friable (open and loose, not compacted), and high in organic matter (full of broken-down and decomposed plants and animals) will hold large amounts of water. We can increase water storage in the ground in a number of ways: by building up the level of organic matter in the soil, which improves its ability to hold water; by increasing the amount of vegetation on the land; and by creating earthworks, like swales and basins, that can increase infiltration and recharge the shallow groundwater. Rain gardens are also effective at slowing and capturing water, using plants that can tolerate sporadically wet conditions.

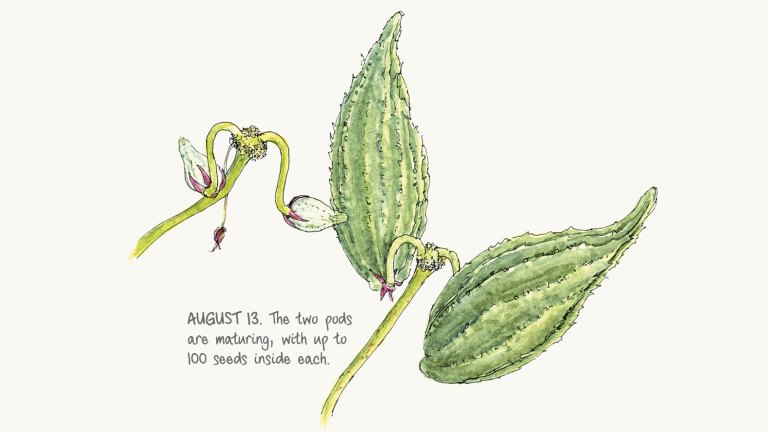

STORE WATER IN VEGETATION. Thick vegetation can hold large quantities of water in several ways. When rain falls into an area with lots of plants, some of the water is held by the leaves and branches, and some is held in the low-growing vegetation close to the ground. (Think about walking out across a field or lawn after a storm. Even when the air has dried, there is quite a bit of moisture in the grass you’re walking through.) Some of this water is slowly released into the soil; some evaporates back into the air. Water is also stored in the living biomass of the plants (which are 90 percent water by weight). In thick vegetation, this amounts to a large reservoir of water.

STORE WATER IN THE GROUND. Small catchments, such as swales and basins, are very effective for catching water and helping it infiltrate the ground, especially if the landscape is designed to slow the water, preventing it from gaining volume or speed as it moves downhill. Small basins can catch and hold water at individual plants or plant groupings; organic mulch, like wood chips in a basin, hold the water and give it time to soak in. Start by going “upstream” to identify the sources of water coming onto the land, and then look for ways to hold the water and let it percolate into the soil. In urban areas, this might mean looking at building roofs as places to intercept and direct the water. Identifying leverage points and intercepting the water early in its flow can have a large net effect.