Notes from Sky Range Ranch: The Adventures of Prue, Part One

What might have caused this deformity? Would she be able to nurse the cow or be able to eat? Would she drown herself if she tried to drink water? Could she live with this problem?

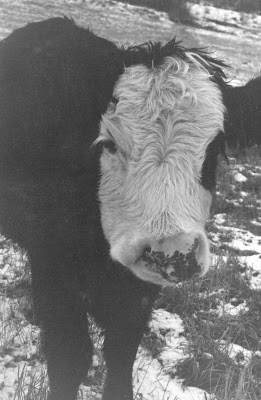

She was born on a cold January morning in 1973. Her mama was an eight-year-old Black Angus cow named Hazel, and her sire was a Hereford named Big John. The birth was easy, and her mama loved her, but when we went out to the calving pen to immerse the newborn calf’s navel stump in iodine, we were startled by her face. Her nose was not properly formed, and there was a big separation below one nostril. We carried her into the house as soon as we’d given Hazel a chance to lick the calf a little; we needed to dry the shivering wet calf by the stove—since it was 15 below zero outside. While drying her with towels, we got a better look at her problem; she had a cleft palate.

We immediately named her Prue (Prudence), after the heroine of a book, Precious Bane, which we had earlier read and enjoyed; the heroine in that book had a harelip. Prue’s right nostril was malformed. The left side of her nose was normal, but the right side was completely open at the bottom; there was nothing separating it from her mouth underneath. There was no roof to her mouth on that side, for about 2 inches back, and the bottom of the nostril opened directly into her mouth. Her little teeth were very crooked.

All sorts of thoughts raced through our heads. What might have caused this deformity? Would she be able to nurse the cow or be able to eat? Would she drown herself if she tried to drink water? Could she live with this problem? Would it be more merciful to end her life? We’d never seen anything like this before, and it was a shock.We asked our veterinarian about it, and he said that deformities like this are rare but sometimes happen because of something the cow ate during early pregnancy—such as lupine. This lovely wildflower often causes calves to have crooked limbs and twisted spines if the cow eats it between 40 and 90 days of gestation. We’d had a few calves born with fused joints and crooked legs because of lupine, but the cleft palate was a new experience for us. Our vet recommended that we put this calf out of her misery.

We quickly discarded that thought, for, in fact, she was in no “misery,” and we accepted the challenge and commitment of trying to raise her in spite of this problem. We fed her some colostrum with a bottle, but it was difficult for her to suck without getting milk up her nose; she had to stop frequently and lick the milk out of that nostril with her tongue. We decided to feed her with a nipple bucket, because that type of nipple was long enough to go clear past the hole in her mouth and the milk could go down her throat instead of into her nose.

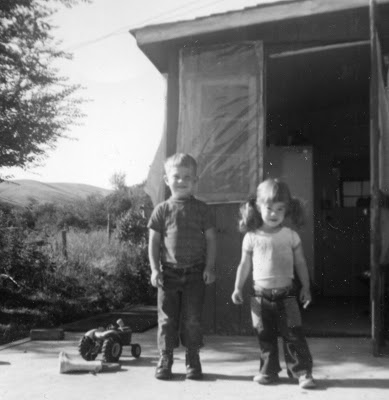

Hazel was very upset with us for stealing her baby and didn’t want anything to do with the milk cow’s calf that we tried to graft onto her. So she went dry for that year. The next spring she had a nice bull calf named Guideon, and he was normal like all the others she’d had (sired by Big John) in the years before Prue. Big John was a good bull, and we had him for 8 years. Hazel had eight calves by him—all normal except for Prue. That convinced us that this wasn’t a genetic defect but probably an accident of gestation, as our veterinarian suspected.Prue had to learn to suck her rubber nipple without getting too much milk foam in her roof-of-the mouth nostril. She was strong, smart, and vigorous, but for the first few days of her life, she lived in a big wooden box in the kitchen because it was still very cold outside and we hadn’t had time to fix her a place to live outdoors. Our children thought it was fun to have a “house calf”; they enjoyed petting her and talking to her. But on the fourth day we quickly made a place for her in a shed. Her vigorous behavior made it necessary.

Lynn and I had been out feeding the cows, and Michael (age 4) and Andrea (age 2) were babysitting Prue in the house. When we came back, Michael was looking out the window, standing on the couch, yelling at us to come quick. Andrea was hiding behind the couch. Prue was curled up sound asleep—on Michael’s pillow on his bed!

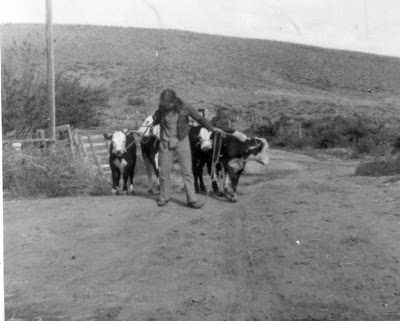

(this photo was taken the fall before she was born).

Prue had jumped out of the box and trotted into the living room to play with the kids, frightening them because she was bigger than they were. As she bucked and ran around the living room, they retreated to safer places. Prue climbed up onto a chair and from there onto Michael’s bed. That cozy calf asleep on the pillow was the funniest thing I’d ever seen, and I couldn’t help but laugh even while I did three loads of laundry to clean up after her. She had made a mess in her box, stepped in it before jumping out, and tracked calf manure onto the rug, through some piles of clothes I’d left on the floor, and through the kids’ toy box, and then she wet the bed!

For several weeks afterward, whenever we were going to bring a cold newborn calf into the house to dry it, two-year-old Andrea would ask if it was a red one or a black one. She didn’t like black ones because they jumped out of the box!

Prue managed to nurse her nipple bucket just fine, but we frequently had to buy new nipples; her sharp, crooked teeth chewed holes in them. We realized that she never could have nursed her mama; Hazel would not have appreciated those sharp teeth. When Prue was three months old, we had to remove one of her teeth because it was hitting the open part of her nostril in the tender roof of her mouth, making it sore. After we pulled that tooth with pliers (a tough pull, since it had a root 1.5 inches long), the raw spot healed.

That summer she lived with the milk cows’ calves. We had two Holstein cows named Baby Doll and Friend; we milked Baby Doll and usually raised extra calves on Friend. Most years Friend raised four calves—hers and Baby Doll’s and any orphans we might happen to have. The calves all lived in a little pasture above the house that summer, and we led them back and forth to the barn with halters. They were fairly well halter broke and easy to lead because they were eager to go to the barn for breakfast and supper, and one person could generally lead all four of them at once.

Thus, Prue was halter trained along with the rest of them, because we brought her to the barn at milking time for her meal, too. We poured fresh milk into her nipple bucket, which hung on the barn wall. She enjoyed the company of the “barn calves,” and by the time she was four months old, she’d sampled their water tub–and learned how to drink without drowning herself. She put her tongue over the hole in the roof of her mouth and sipped slowly, blowing lots of bubbles as she drank. She was the noisiest, slowest, slurpiest drinker on the ranch, but she had that problem solved.

[to be continued…]

Heather Smith Thomas raises horses and cattle on her family ranch in Salmon, Idaho. She writes for numerous horse magazines and is the author of several books on horses and cattle farming, including Storey’s Guide to Raising Horses, Storey’s Guide to Training Horses, Stable Smarts, The Horse Conformation Handbook, Your Calf, Getting Started with Beef and Dairy Cattle, Storey’s Guide to Raising Beef Cattle, Essential Guide to Calving, and The Cattle Health Handbook.

The Cattle Health Handbook is the essential medical reference for farmers and ranchers confronting day-to-day bovine health issues. Heather Smith Thomas, an expert on livestock with decades of first-hand experience, covers every routine situation — and many not-so-common problems — likely to arise on a cattle ranch or dairy farm. Three broad sections cover common diseases, ailments specific to certain body systems, and other ailments and injuries.