Notes from Sky Range Ranch: Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Calf

Over the past 45 years, our kitchen has served as an intensive care unit for baby calves. Some needed temporary warming in subzero weather or emergency treatment after a traumatic birth or during acute illness. Premature babies that were too fragile to be outdoors spent days or weeks in the house. Some of our “house calves” became family pets.

The first “preemie” to spend time in our house was born 5 weeks early, when our cows were still out on fall pasture, a half section of mountain pasture that we use with dry cows after weaning their calves. It sustains them until it snows under in late November or December. Then we bring them down to the fields until they get close to calving. About Christmastime we put them in closer pastures near the “maternity” pens and barns.

for drying and warming cold newborns.

One December night about 35 years ago, we had a snowstorm and decided to bring the cows down from the mountain the next day. My husband Lynn drove our jeep up there to call the cows. They come when called, since they know they will be fed or moved to new pasture. I rode up the other canyon and started gathering cows in that area. Up in the farthest corner, I found a group of cows — and a coyote sitting on a rock, watching them. I soon discovered what the coyote was looking at: a tiny new calf. The cow was standing there, guarding her baby.

(left of center in this photo, just below snow line) when the snow was a lot deeper.

is walking ahead of this group of cows, calling and leading them down.

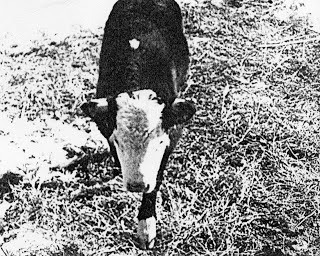

She’d calved at least 5 weeks too early, and the calf weighed about 20 pounds; he was one-fourth the size he should have been, and his hair was short and fine, like velvet. He was very cold. The temperature was only 6 degrees that morning; he was lucky to be alive.

I thought about putting the calf on my saddle and carrying him over the hill to the jeep but wasn’t sure if my skittish young gelding would tolerate something that novel. So instead, I chased the coyote away, then galloped over the mountain to find Lynn. I told him about the calf, and he drove the jeep up the canyon, until it got too steep and rocky. He hiked the rest of the way, through the snow. He carried the calf down to the jeep, with Mama at his heels, and I herded the other cows along behind them. The calf rode on the jeep seat with Lynn the rest of the way home.

The baby was too frail to live with Mama in the barn; he was showing signs of pneumonia after being chilled and had difficulty breathing. When we got the cattle home, we brought the little fellow into the house to warm up and gave him an injection of antibiotics. When our two young children, Michael and Andrea, came home from school, they named the calf Rudolph, because of his red frostbitten nose.

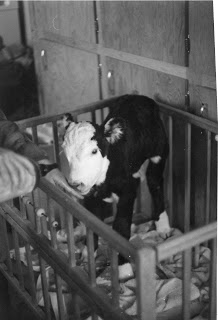

We kept Rudolph in the kitchen in Andrea’s old baby crib; he was so small he couldn’t jump out. Andrea fed him a bottle of colostrum, and for several days afterward we fed and treated Rudolph every few hours around the clock. It was hard for him to suck his bottle because he was using all his energy just fighting to breathe.

By Christmastime he was winning his battle against pneumonia; his high fever was coming down. School was out for Christmas vacation, and Michael and Andrea were happy to be home helping take care of Rudolph. He was feeling better and tried to jump around in the small crib. He didn’t have room for exercise, so we let him out of the crib for a few minutes to play and buck. He liked that so much that we let him out for a few minutes every day.

The living room was a perfect place for his frolics. His little feet had good traction on the rug, much better than on the slick kitchen floor. We usually let him out of the crib in the evenings, when we were done with outdoor chores and the whole family could watch. We always had a jar handy, in case Rudolph needed to take a leak.

Lynn would lift Rudolph out of the crib and carry him into the living room, and the calf’s little legs would churn the air eagerly in anticipation; he wanted to get down on the floor and run. He’d take off as soon as his feet touched the carpet, bucking, snorting, and charging around the room. It took all of us to guard things we didn’t want him to crash into — such as the record player and the Christmas tree. One of us would keep him away from the hot stove, and Andrea would head him off if he made a dash for the dining room. If we couldn’t catch him, he zoomed out onto the linoleum floor, like little Bambi on the ice pond — sliding out of control or doing the splits with his hind legs.

On the carpet he had good footing and got up a lot of speed; a few times he galloped up onto the couch. He attacked anyone who tried to play games with him, knocking heads with Andrea or Michael and showing us how tough he was. He was so funny — we’d laugh so hard we rolled on the floor. The Christmas tree fascinated him, and if we weren’t guarding it closely, he’d try to eat the branches or knock off ornaments. Sometimes we had to limit his playtime so he wouldn’t get tired and out of breath from running and bucking.

After 3 weeks he outgrew the crib and was trying to climb out. He still wasn’t “full term” yet in size or time, but he was closing the gap. In early January Michael and Andrea helped Lynn fix a warm corner for Rudolph out in the barn. We were sad to see him go when Lynn carried him out the back door, but Rudolph had more room to run and play out there and liked it better than the crib. Andrea still fed him his bottle several times a day, except when she was at school.

When weather got warmer, we made a pen for Rudolph outside. He grew large and strong, and soon the kids had to be careful playing games with him — he was much bigger than they were. Playfully butting heads with a 20-pound calf had been fun, but when he grew to be 500 pounds, that was something else.

Even though he started out as the smallest calf, he was one of the larger steers in our herd that fall. It was difficult for the kids when it came time to sell him. We often wondered if he remembered his early weeks as a house calf, chasing us around while he played “king of the living room.” Maybe. But no way would he ever fit into that crib again!

Heather Smith Thomas raises horses and cattle on her family ranch in Salmon, Idaho. She writes for numerous horse magazines and is the author of several books on horses and cattle farming, including Storey’s Guide to Raising Horses, Storey’s Guide to Training Horses, Stable Smarts, The Horse Conformation Handbook, Your Calf, Getting Started with Beef and Dairy Cattle, Storey’s Guide to Raising Beef Cattle, Essential Guide to Calving, and The Cattle Health Handbook. You can read all her Notes from Sky Range Ranch posts here.

The Cattle Health Handbook is the essential medical reference for farmers and ranchers confronting day-to-day bovine health issues. Heather Smith Thomas, an expert on livestock with decades of first-hand experience, covers every routine situation — and many not-so-common problems — likely to arise on a cattle ranch or dairy farm. Three broad sections cover common diseases, ailments specific to certain body systems, and other ailments and injuries.