The Evolution of the North American Axe

It may be a simple hand tool, but over the course of two centuries, the axe became the driving force behind expansion and industry in North America.

Because the axe is such a simple tool — it’s essentially a wedge with an edge — it was affordable to produce and acquire, enabling early settlers from Europe to carve out an agrarian existence from the forest. The axe was their ticket to a strong shelter, open ground for cultivation, a heat source, and even personal protection.

It could be argued that no tool has changed the American landscape more than the axe; the landscape also changed the tool.

The European Axe Comes to North America

When Captain John Smith arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 he was surprised to see that a hatchet known as the “trade axe” or tomahawk was a well-established form of currency. These early axes were French and Portuguese in origin, and were valued by the Native Americans as a versatile tool and symbol of heraldry. Driving the trade axe barter system was an insatiable appetite for furs in Europe, driven largely by French, Portuguese, and later Russian traders. However, the European axes would quickly morph into a distinctly American tool, as demanded by the rugged and wild landscape of North America.

When European settlers arrived in the forests of eastern North America, they quickly discovered that the smaller, lighter-weight European axes they had brought with them — which they had used on small-diameter coppiced trees back home — weren’t up to the task of felling large-diameter timber that was better measured in feet than inches.

These early settlers made two modifications that resulted in the modern felling axe:

A heavier poll. First, the settlers added substantial weight to the poll of the axe. This additional weight meant that the woodsman didn’t have to swing as hard and could instead let the weight of the axe do the work. More weight behind the handle also meant better balance, which made for truer swings.

A shorter bit. The settlers also shortened the bit (the cutting edge). Early European axes had a wide cutting edge, which made for an effective battle weapon but didn’t allow for concentrated penetration when it came to chopping wood.

By the late eighteenth century, felling axes began developing regional identities as blacksmiths and lumberjacks named their axes after the places they were made; Connecticut, Michigan, Maine, and Pennsylvania became popular patterns. As they replaced the blacksmith, modern forges began to produce dozens of patterns for different uses and enough pattern choices to satisfy lumberjacks from coast to coast.

Building Shelter and Girdling Trees

Upon its entry to the “New World,” the axe wasn’t the tool of the lumberjack; it was the tool of the pioneer, a means of providing shelter and fuel. The American felling axe allowed homesteaders to clear land, build and heat their cabins, fence their livestock, and cook their food. With an axe, a basic cabin could be constructed in a week out of pole-sized timber. The notches of these early cabins were shallow and crude; the spaces between the logs were chinked with clay, plaster, oakum, moss, or anything that would reduce the draft and help keep the heat. The head of an axe was used to push the material to the center of the logs where it’s tightest, to help close the gap.

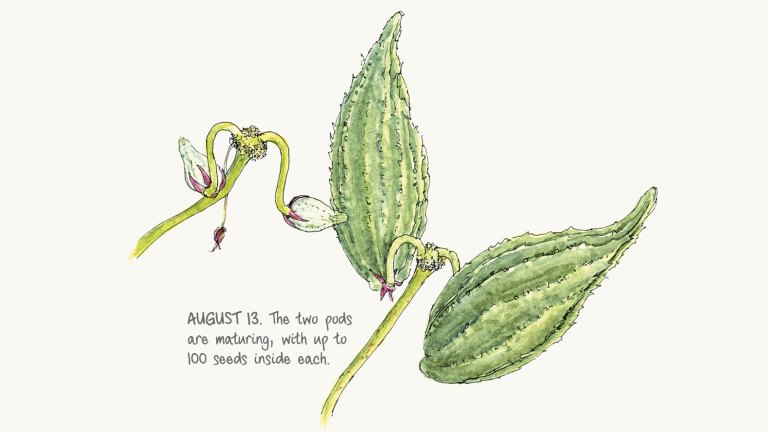

Once the cabin was established, the axe was put to use girdling trees. By using the axe to scribe a ring around the tree, nutrients were cut off from the canopy, leaving a standing dead tree. This standing firewood was an important part of how the settlers kept warm in the winter, but on a grander scale allowed for massive burning of dead and dry forests that could then be converted to agricultural lands.

By 1900, European settlers had managed to clear nearly 500,000,000 acres of forestland with the axe.

1965: The End of the Golden Axe Era

For more than two centuries, the axe occupied a central role in settling, and literally building, America. From the Civil War to the mid-1960s, the American axe was in high production. However, by the early 1960s, it became clear that the axe was moving from a starring role to a minor character in the American landscape. The transition to chainsaws, migration from rural to suburban environments, and decline of wood heat all contributed to the end of the golden era of axes.

In an effort to stay afloat, axe manufacturers responded by merging companies, relocating to Asia and South America, and diversifying by making other tools. For those manufacturers who survived, it became clear that the American consumer was no longer a lumberjack who depended on a quality tool for his livelihood, and was instead more likely a suburbanite who was apt to use the axe for grubbing out an ornamental shrub in the lawn, or splitting a few pieces of wood on a summer camping trip. This led to a race to the bottom, resulting in cheap, inferior axes.

Modern Axes

The recent interest in traditional tools has inspired independent blacksmiths, boutique axe makers who turn out a few dozen axes per year, and a few mass-producers of premium axes that are specifically designed for discerning woodsmen. Even large-scale American tool companies, such as Council Tool, have developed premium axes to bring quality axe-making back to America.

For some, the American axe has come to represent brute strength, the taming of nature, and even violence (Lizzie Borden comes to mind). But it’s also a symbol of hard work, honesty, and simplicity. It’s a tool that combines strength, utility, and aesthetic appeal — that’s just part of what makes them so fascinating.

Text excerpted and adapted from American Axe © Brett Mcleod.

From hand-forged axes of the Viking conquests to the American homesteader’s felling axe, this is a tool that has shaped human history like few others. American Axe pays tribute to this iconic instrument of settlement and industry, with rich history, stunning photography, and profiles of the most collectible vintage axes such as The Woodslasher, Keen Cutter, and True Temper Perfect. Combining his experiences as a forester, axe collector, and former competitive lumberjack, author Brett McLeod conveys the allure of this deceptively simple woodcutting implement and celebrates the resurging interest in its story and use.