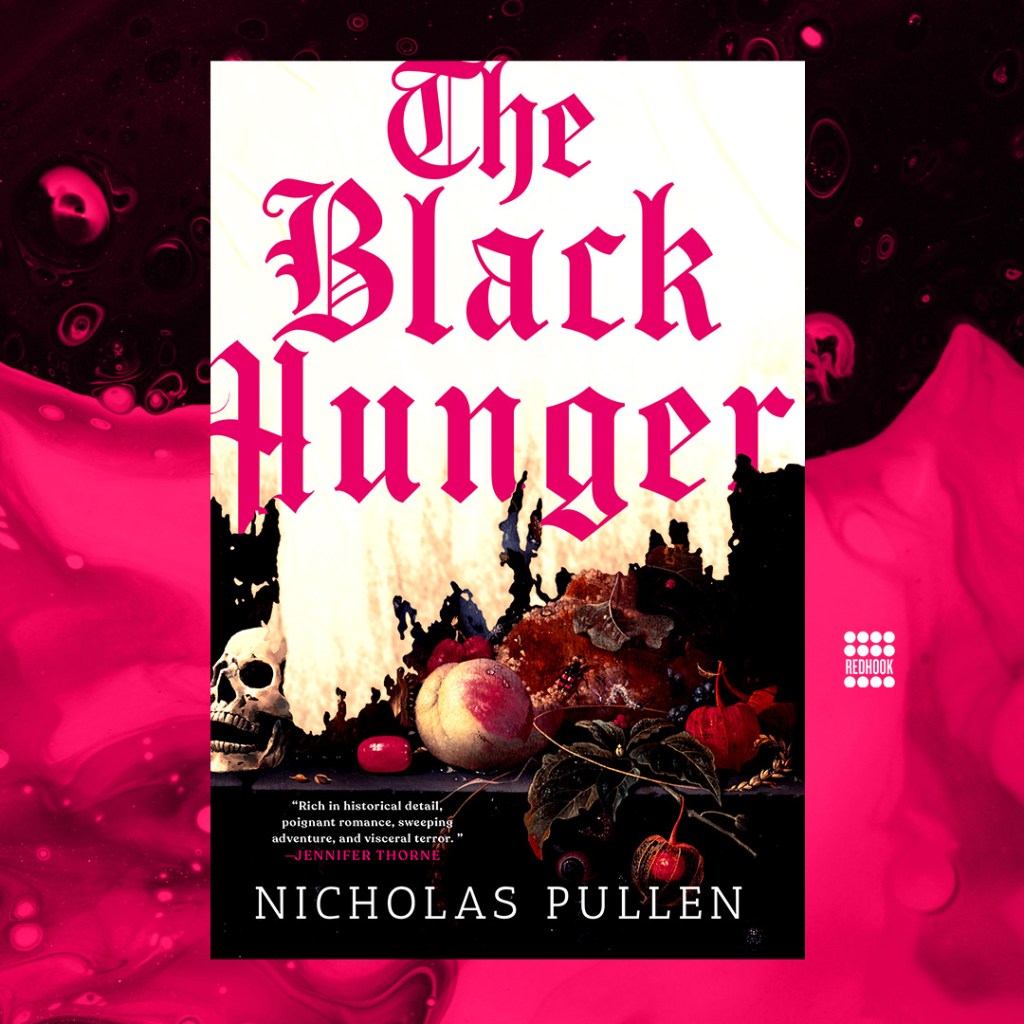

The Black Hunger by Nicholas Pullen: Exclusive Excerpt

A spine-tingling, queer gothic horror debut where two men are drawn into an otherworldly spiral, and a journey that will only end when they reach the darkest part of the human soul.

Read an excerpt of The Black Hunger, on sale October 8th below!

And so we rode down the mountain in silence. The pilgrims had all gone home or were sequestered within the monastery walls. The prayer flags snapped in the wind, which was rising, and clouds were pouring off the mountains in the far distance, where trails of blowing snow stood out from the highest peaks like the trumpets of destroying angels. There was only the sound of our horses’ hooves and the rising drone of the wind in our ears. About an hour later, we were at my bungalow. Prince Sidkeong looked shaken. I asked him if he would do me the honour of taking a cup of tea, and he nodded and dismounted. Grooms took the horses, and we entered the bungalow. I was immensely relieved at the familiar furniture and the mercifully bare walls, with their benign prints of the Lake District and the Cotswolds faded by the mountain sun. Garrett opened the door from the kitchen, saw that I was with the Prince and inclined his head, his eyes betraying his surprise and mild alarm at the hushed air we could not conceal.

“Tea, Benson,” I said abruptly, and he ducked back into the kitchen. The Prince and I sat in silence until Garrett brought us the tea in the silver service. I poured the Prince a cup, and he sipped it. We sat in silence for a while. Eventually I broke it.

“I had not heard the story quite like that before.”

“No.”

“Is that . . . its true version.”

“No!” He was emphatic. “That is not it. The version you know already is the correct one.” The version where Shakyamuni sets forth to achieve enlightenment through self‑ denial and eventually becomes the Buddha.

“Then where does this version come from?”

“It is a version that has always been current, in one form or another since ancient times. The sages have always known of its existence, but only one sage has ever worshipped Shakyamuni in that form. Vadakha was his name.” I remembered my Sanskrit, and jumped as I recalled that I had read the name before, at Oxford.

“Executioner?”

“Yes, that is the name he chose. He was leader of the Dhaumri Karoti.”

“The Blackeners.”

“Yes, that is as good a translation as any. In the few forbidden texts left where they are spoken of at all, they are also sometimes known as the Black Helmets.” Most Buddhist sects in Tibet are known informally by the hats that they wear. “They are supposed to have ridden to battle in black armour.”

“Ridden to battle?”

“Yes. The Dhaumri Karoti were devoted to the destruction of the world. You know the story of the Buddha’s enlightenment, under the Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya?” I nodded. The Buddha had meditated, and Maura, the tempter demon of desire, had attacked him with his combined hordes of demons. The Buddha had defeated him, touching the earth to demonstrate that by its power, and through its witness Maura was defeated.

“The Dhaumri Karoti believe . . . believed . . . that Lord Buddha did not defeat Maura that day. They believed that instead he made a pact with the Demon King. The only way to end suffering was to wipe out existence. To destroy all sentient beings, and to leave the earth a dead, barren wasteland, devoid of life, which ultimately, for them, is the cause of suffering. To be alive is to suffer. So the only way to end suffering forever is to . . . well . . . ” I nodded. It was clear enough. “The Dhaumri Karoti take the ultimate goal of Buddhist practice quite literally. Nirvana, in Sanskrit, means specifically to snuff out a candle. For the Blackeners, that did not . . . does not mean release from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. It means the end of birth, death and rebirth. The snuffing out of all life on earth.”

The night was getting colder outside, and the wind was howling off the mountains now. A light snow was whipping through the shaft s of light from my sitting room as they spread feebly through the darkness outside. For the briefest instant, each snowflake hurtled through the shaft of light, and then it was gone again, swallowed by the all‑ consuming blackness. In that moment they were metaphors for life itself. Garrett had sidled into the room and built a fire in the hearth. He was taking his time with it, I knew. He wanted to hear. Prince Sidkeong seemed to notice him there, and paused, waiting for him to leave. Aft er the fire was lit, and Garrett had returned to the kitchen, to listen through the door, as he told me later, the Prince continued.

“They were shouted down in the early Buddhist councils, and their doctrines were repudiated and expunged from the Pāli Canon. But they did not give up. They merely went underground, recognising each other by arcane signs and black magic. They came to Tibet with the early Buddhist missionaries at the invitation of the Tibetan king Trisong Detsen, when Buddhism first arrived in these mountains. Their great sage was the third of the missionaries to come to Tibet. Efforts have been made to expunge him from the records. We no longer remember his name, and we pretend to our children that there were only two Buddhist masters who came at the king’s request. But there were three. And the third was of the Dhaumri Karoti. He quickly spread his cult in secret, hiding themselves mainly within the Nyingma school, and establishing their lineages in horrible mockery of the good and noble order they had invaded like a parasite. Over the centuries they built their power, practising dark magic and discovering many horrible things in alliance with the gods and demons who did not surrender to Buddha. One monastery, in particular, whose name has been expunged, became colonised entirely by their filth, and they used it to research unspeakable depravities and devise monstrous plans. Among the corruptions they discovered was the lesson that if they consumed human flesh they would be granted great spiritual and physical power. They would for ever be cursed by the desire for more and more of it, and this hunger, the Black Hunger, they called it, would never be satisfied. This is also known by many of the tribes in North America, who know the power of what they call the Wendigo demon. I have been told they have developed powerful magic of their own to counter and snuff out the Hunger before it can spread. But the Dhaumri Karoti know that if this hunger is controlled through the discipline of tantric meditation, it can be harnessed to grant he who hungers almost limitless power; over his own body, over other men, and over nature itself.”

“Good God.” I had no idea what to say. “How did they spread in secret?”

“We do not know the names of their lamas and their lineage holders. Once they were powerful and respected members of our Buddhist orders, and their lineages were extant and well‑documented, but we have erased them. From your classics you must remember the Roman punishment of damnatio memoriae?”

“Yes, of course. The destruction of the memory. Erasure. Forgetting.”

“Believe me when I tell you that you do not wish to know the names of their lineage holders, their lamas, their abbots. It is better that no one ever know.”

“I do believe you.” I was clutching my teacup with both hands. Sidkeong swallowed and continued his tale.

“By the twelfth century, they felt they were ready. They sent their foremost apostle, whose name has also been expunged, to Mongolia, and they used their sorcery to aid the man who would become Genghis Khan in unifying the Mongolian tribes, who they felt would be the hammer with which they would destroy a suffering world. Th ere were even rumours that they sent emissaries to those parts of the world that lay beyond the oceans, whose existence they had divined in their oracles, and made allies there as well. Dhaumri Karoti lamas were among the Tibetan lamas at the court of the Mongol Khan, and they were responsible for much of the brutality that Genghis inflicted upon a suffering world, over the desperate objections of the true lamas. But when the Great Khan died, gradually the empire fell into decay. And years later, the noble Kublai Khan discovered the existence of the sect, and had them ripped out from his court, root and branch. He organised a great inquisition, I believe you would call it, and he had them hunted down and killed, their scriptures burned, their monasteries destroyed and their memory expunged, the very mention of their name interdicted by pain of death. Thankfully, by this point the Dalai Lama had also been born into the world. Some centuries later, the third Dalai Lama entered into an alliance with a Mongol warlord named Altan Khan. A pact was made between them. The Dalai Lama recognised Altan Khan as a reincarnation of the great Kublai, and, in return, Altan Khan spread Buddhism throughout Mongolia, rooting out the Dhaumri Karoti and their perverted version of the faith there as well. The Dalai Lama, you must understand, is the incarnation of Chenrezig, Avalokiteśvara, the Boddhisatva of compassion. He has been sent into this world to hold the Dhaumri Karoti at bay.

“They were utterly and finally vanquished by the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, whose power was vast enough to root them out of the few mountain monasteries they still defended and concealed with dark magic. Many abbots and high lamas, he revealed, had been Dhaumri Karoti. They were executed. The Sixth Dalai Lama rooted out their scriptures and burned them and expunged all memory of them from the sacred texts. Magic was performed to seal their power, and powerful charms protect Tibet, India, Mongolia and China from their influence. The Dalai Lama maintains their power, though few remember this, because the memory was so thoroughly expunged. Th rough his meditation and prayer and maintenance of the defences, he keeps the Dhaumri Karoti at bay. But they survived somehow. I know this now. Because you do.”

“What?”

“When you asked the Abbot about the Dhaumri Karoti you fulfilled a prophecy, even though you did not know it. It was widely known among the various sects that if an Abbot’s ears were ever profaned by the name of the Dreaded Sect, particularly by a foreigner, it would mean that they had not been vanquished. That they have merely been biding their time, waiting for the moment to strike again.”

But surely . . . you don’t mean . . . the British?” I was incredulous.

“No. If it were the British, we would have known by now. You are a godless people. Your Christianity is vestigial, a matter of cucumber sandwiches and bad tea. You believe in science and reason and progress, to the exclusion of all else. It is your great strength and your great weakness. You lack the faith in the supernatural to harbour a sect like this in your society.”

“Yes, well . . . I suppose so.”

“When the Great Fifth purged the Dhaumri Karoti, there were areas far to the north that were beyond his reach. The Buryat Mongols fled to Siberia and carried the teachings with them there. The Dalai Lama had no influence in those cold, northern wastes. And the Oirats and Khalymyks went even further away, to European Russia, where they remain to this day.”

“Russia, you say?”

“Yes. If the Dhaumri Karoti have survived, they have survived in Russia. There have been Buddhists there for centuries. Often among the Tsar’s most loyal subjects. For the last few decades, there has even been a Russian monk at the court of the Dalai Lama, seeking to extend the Tsar’s influence there, at the expense of you British. Th ere are many in Tibet who would prefer the Tsar’s protection to that of your own sovereign.” This I knew. Mr Bell had alluded to it more than once. The monk’s name was Ivan Dorjiev.

“So now that this name has been spoken . . . you believe . . . ”

“I do not know what I believe. I know only what I was told about the prophecy by my father as a child, when he was instructing me in the kingdom’s secrets.”

“Well then . . . what should we do?” He looked at me.

“For the present, nothing.” I was immensely relieved. I was worried he would go to Mr Bell with this and drag me along as an accomplice. “We will wait and see. His Holiness is coming to Darjeeling. This may be fortuitous. We will consult him. He will know what to do.” A silence fell. It was now approaching midnight. The Prince finished his cup of tea and stood up.

“You British really do make a mockery of tea with this insipid concoction.”

I laughed. “I’m afraid I feel much the same way about butter tea.” This was the Tibetan version of the stuff . Made with yak butter, and really more of a light soup than anything an Englishman would recognise as tea.

“You may call butter tea many things, but I do not believe you can justly call it insipid.” He smiled. I rang the bell and Garrett appeared. “Thank you for the tea, John. I’ll see myself out. For the time being, I would ask you to say nothing of what I have told you. We will make discreet enquiries before His Holiness arrives in Sikkim.”

“Well, it feels wrong to say thank you for taking me to the monastery today. I cannot say I enjoyed it. But thank you all the same.” Garrett helped the Prince on with his boots, and held the door for him. When he left , and the sound of his hooves was clattering up the driveway, there was a heavy silence.

“What the devil was that, John?” It was serious. He had called me John.

“I haven’t the faintest idea.” He had heard much of what had passed between us, but I told him about the meeting at the monastery, and the Abbot’s crazed version of the Buddha story.

“Well. There’s a lot of foolishness, for certain.” This was the word he had used for any religion, or anything to do with the supernatural, since we were thirteen. There was a pause. “You don’t . . . believe any of it, do you?” It was easy enough to believe in the wan light of the paraffin lamps, with the Himalayan winds howling outside through the darkness.

“I don’t know. Let’s go to bed and see how we feel in the morning.”

And we did.

Hungry for More? The Black Hunger is available on October 8th, 2024.

A spine-tingling, queer gothic horror novel where two men are drawn into an otherworldly spiral.

“A gothic masterpiece. A devastating exploration of humanity’s capacity for evil.” —Sunyi Dean, author of The Book Eaters

John Sackville will soon be dead. Shadows writhe in the corners of his cell as he mourns the death of his secret lover and as the gnawing hunger inside him grows impossible to ignore.

He must write his last testament before it is too late.

The story he tells will take us to the darkest part of the human soul. It is a tale of otherworldly creatures, ancient cults, and a terrifying journey from the stone circles of Scotland to the icy peaks of Tibet.

It is a tale that will take us to the end of the world.

“A phenomenal book full of rich historical detail, occult mysticism, and slow, creeping horror. A triumph that should be on your reading list.” —Thomas D. Lee, author of Perilous Times

“The Black Hunger reveals its horrors inch by devastating inch.” —Molly O’Neill, author of Greenteeth

“A terrifying gothic journey to the place where the very cruelest, hungriest creatures hide in the snow, and wear our faces. This is a magisterial debut.” —Michael Rowe, author of Wild Fell

“Rich in historical detail, poignant romance, sweeping adventure, and visceral terror.” —Jennifer Thorne, author of Diavola