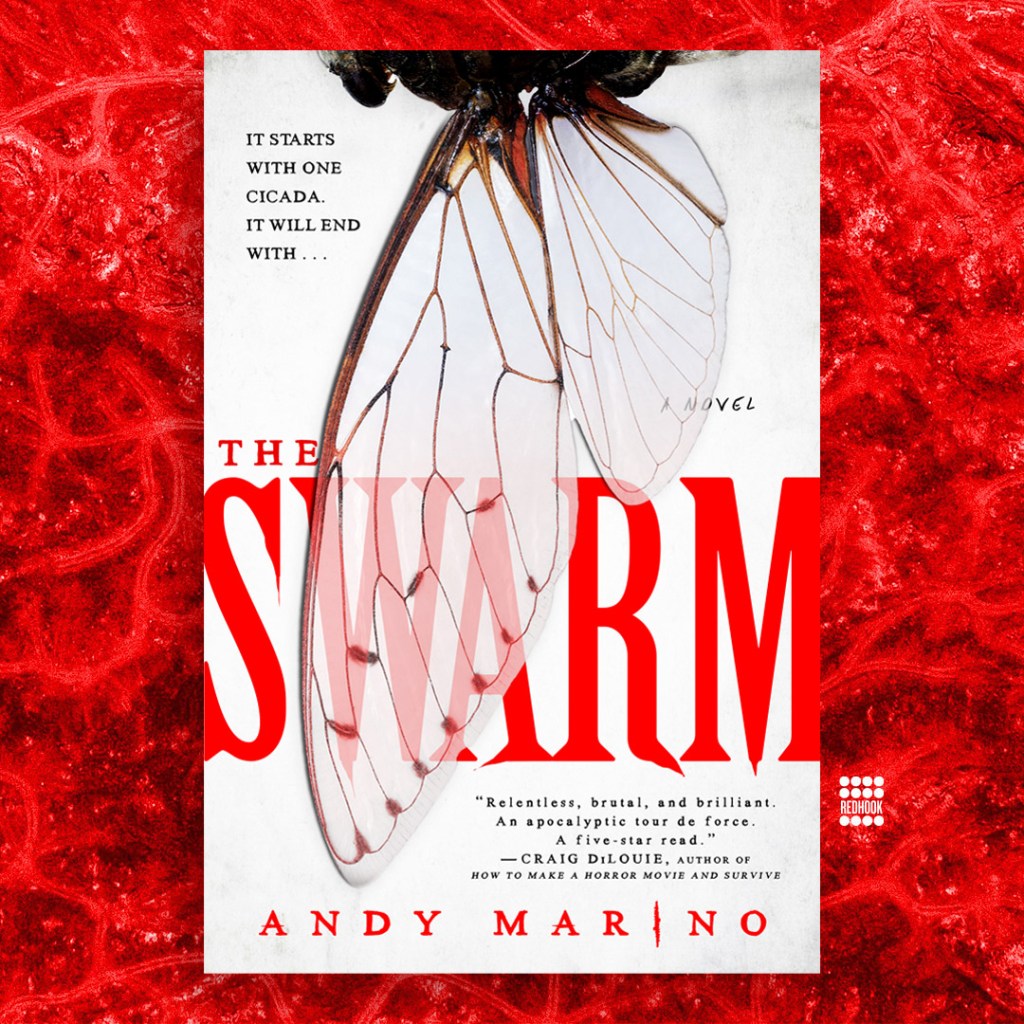

Excerpt: THE SWARM by Andy Marino

From the bizarre and audacious imagination of horror author Andy Marino comes a harrowing tale of the insect that will herald the apocalypse…

Read the first two chapters of The Swarm, on sale November 5, below!

1

Hoarder houses are like happy families: all alike. Detective Vicky Paterson holds her breath. There will be cat piss.

With a gloved hand she pushes the front door open as far as it will go. The old wood, swollen in the summer heat, creaks in its frame. In the bad light of the foyer she can see a canyon of stacked magazines, boxes of yard-sale kitsch, the glint of scattered doll eyes. A tangled mess of kitchen playsets, their plastic skillets caked in charred lumps.

Did someone actually use them to cook?

Vicky’s eyes water. It’s only a matter of time before she’ll have to take a breath. Barely inside and particulate matter sticks to her skin. Her heebie-jeebies are no joke. Two swipes of menthol ChapStick under her nose and she risks an inhale.

Vicky knows this, right here, is the best it’s going to get, just inside the door, a few feet from the Adirondack mountain air. One last glance at the two uniforms lighting cigarettes by the cruiser parked down the gravel path reveals queasy upset all over their faces. Rookies on the graveyard shift doing a wellness check, not expecting this.

Whatever this is.

Vicky shuffles fully inside. Her vinyl shoe covers make a crispy sound in the wee-hours silence. Filth’s in sedimentary layers on the floor: rat droppings, fur, dust, pebbles, beads, petrified food scraps, kibble. A single lamp is perched atop a tower of board game boxes, their labels faded and yellowed. Old-school Clue and Monopoly along with more obscure titles she’s never heard of. One’s called Jiminy Cracker Skin.

It’s a miracle that electricity still runs to this place. Vicky supposes whichever relative called in the wellness check keeps the utility bills up to date. Without any kind of judgment, she wonders why this daughter or brother or niece didn’t have the resident old lady committed.

Well, maybe they did. Seventy-two-hour hold in the overcrowded, underfunded psych ward and then pop goes the weasel. That peculiar combination of maddening stubbornness and heartbreaking mental illness that alienates folks with hoarder tendencies. The old lady’s burning resentment that she was ever committed in the first place. The slow dispersal of fed-up friends and family. The cycle of ingrained habit and solitude that begets itself. The ruin. The junk. The cat piss.

Vicky moves slowly past typewriters and candles, holiday lights and nutcrackers. A crooked sign says bless this mess, a heavy-handed detail no one will believe. Books and moist cardboard fused into unholy lumps, stuffed animals and clothes with yellowed tags attached—all of it conspires to render the hallway at a strange angle. Vicky feels like she’s treading the deck of a ship listing hard to port. Nausea rises. She makes a mental note to ask the ME for some of that medical-grade menthol rub. ChapStick is useless. Ten million cats used this place as their litter box.

A muffled conversation drifts in. The uniforms outside, embellishing their war story. She turns a corner past a pair of end tables stacked atop an ottoman, all draped in cobwebs. She tries to remember the name of the Dickensian lady in the wedding dress in the crumbling mansion. The drama club at Halcott Central did that play back when she was a teenager, and everyone was forced to attend an afternoon performance. It felt like it was six hours long.

Vicky turns another corner and squeezes through the middle of what was once a living room. Clear plastic recycling bags stuffed with odds and ends rise from an adjustable hospital bed. The light fades. The stench grows. A cold pressure grips her head, at odds with the stifling air. She clicks on her flashlight. The beam plays along old iron bed frames, soiled blankets, frozen dinners bought in bulk. The toe of her shoe catches on a rain slicker, and something scuttles across her path. She freezes, spooked, hand on her holstered Glock, until she hears the critter burrow deeper into the labyrinth. Her flashlight illuminates a rare section of exposed wall. At first it looks burnt. Then she realizes it’s mold, black and speckled and moist. An oily sheen covers everything, as if the rotten drywall is sweating. She makes a note to ask the ME for a hazmat suit too.

Vicky moves into the dining room. An archway, perhaps once grand, is festooned with threadbare garlands. Here she stops. Her mouth opens—something she’s been trying hard to avoid. She sucks in a breath. A new and pungent stench is in the back of her throat now, the cloying, hot-garbage odor of decay. The only smell on earth that delivers a synesthetic rush to her head, all the drab and muted colors of death popping like sad fireworks behind her eyes.

She smears more ChapStick across her upper lip and takes in the scene.

This perfectly square and windowless room has been cleared out, except for a long dining table that shines as if doused in lemon Pledge. Lingering patches of torn carpet cling to ancient linoleum. She makes note of the sheer effort it must have taken to remove a thousand pounds of junk from the room. This had not been accomplished in a single hasty visit.

The old woman is lying on the table, dressed in a clean floral housecoat. Her hands are folded across her stomach. There is no immediate indication of violence. What strikes Vicky about the scene is the total lack of that lurid snapshot quality of most homicides. Rage and terror in the rude angles of splayed limbs, fury scrawled across walls in great spatters of blood. Not here. Here there is funereal peace.

Vicky sweeps her light across the bare, decrepit walls, then the ceiling. No sign of a light switch or overhead fixture. No lamps either. She’ll have to be careful. She keeps the light trained on the floor as she walks to the table, careful not to disrupt any errant debris. At the table’s edge, she shifts the light to the woman’s face. Mottled skin is drawn tight against the cheekbones. The lips are stretched into a grimace that Vicky chalks up to gravity, not pain. Her heart begins to pound. Eight years into her career in the Fort Halcott Police Department—the last two in Major Crimes—and still, the proximity to death gets its claws into her.

She can already feel tomorrow’s cold sweat, waking to the hint of afternoon light slinking around the edges of her blackout curtains, the sinewy tenderness of the old woman’s frail throat invading the corners of her mind.

But for now she has a job to do. Being alone in this place is unpleasant, but she’s grateful for the chance to perform a thorough, solitary appraisal before someone careless disturbs her scene. She takes a video of the corpse from head to toe, panning slowly, following the flashlight. The mental notes tick themselves off. Snap judgments and fledgling theories arrive and she acknowledges their presence and lets them drift away. Vicky’s Buddhist shit, her partner calls it. A leaf on the wind or whatever.

The woman’s bald head captures her attention. There are no wispy strands of hair, but there is what appears to be soft stubble. Peach fuzz. Shaved, Vicky thinks. With clippers. No obvious signs of violence on the scalp, face, or neck. She notes again the spotless nature of the housecoat, at least on the fabric that covers the torso. Fluids have begun to pool in the lower half. She pauses on the woman’s folded hands. There’s something odd about them. Vicky has to look for a long time before it hits her: All ten fingernails are gone. Not clipped or torn. Removed entirely. On a hunch, she pans down to the bare feet.

The toenails are missing too, nail beds pale and shriveled. No blood. The killer or killers were careful, almost surgical, in their precision here.

A sudden feverish rush forces her to grip the edge of the table. She lets the dizzy spell wash over her and waits for it to pass. Methodical killings aren’t exactly a staple of Fort Halcott. New York’s twenty-sixth largest city (population sixty-four thousand, just behind Schenectady and with a healthy lead on Utica) sees its share of robberies gone wrong, wannabe-gang killings, the odd domestic that escalates to murder, some darker-than-garden-variety drunken mayhem.

This is something different. The thought of a man standing right where she is now, bending over the corpse, taking his time with various grooming tools, cranks up those heebie-jeebies. She kills the video and pockets the phone. Then she takes a moment to raise the flashlight and aim the beam down the hall. Light settles into the nooks of the hoard. Plastic organizers draped in ancient linens. Curtain rods and fireplace tools. Hundreds of paperbacks. She dispels the notion that she’s being watched.

All alone, Vicky.

Another sweep of the room reveals nothing new. There’s only one more place to look. She kneels down to peek under the table.

“Dang.”

Three small cardboard boxes are lined up in a neat row. Their flaps are closed but not sealed.

Down on one knee, she pauses. This crime scene is already doused in off-kilter energy. A profiler would call it ritualistic. This likely won’t be the only killing. It might not even be the first. It certainly won’t be the last. There’s also an element of all this that’s nagging her and has nothing to do with the death itself. She can’t yet give this hunch form and meaning.

“Oh, dang it all,” she says. Tentatively, with a gloved hand, she flips up the first box’s flaps. She leans forward, ducking fully under the table, and peers in. Within the cone of light sits a nest of gray hair streaked with white.

So the killer shaves the old lady’s head and tucks the hair neatly into a box like he’s prepping an Easter basket with a bed of grass.

Her whole body is tingling, pins and needles in her fingers and toes. All over Fort Halcott, people are settling in for an air-conditioned slumber, cuing up late-night shows, raiding fridges for midnight snacks. Normalcy abounds. And then there’s this.

She reaches for the second box and steels herself. She thinks she knows what it’s going to be, but it doesn’t make the process of discovery any less harrowing. Up go the flaps, and there’s the small pile of gnarled, corroded nails. Thick and amber-colored, fungal in a way that breaks her heart. Not a drop of blood. A word comes to her and she wants to dismiss it but she can’t. Harvested. At the third box, she pauses. Hair and nails. What else could be missing?

Her phone buzzes in her pocket. She ignores it. If it’s the babysitter she’ll call back in a minute. Her hand is poised over the third box.

“Just flippin’ do it,” she tells herself. Her fingers go to work. The light shines in. Her sharp intake of breath pulls foul air down her throat. “Oh no.”

The box contains a bloodless pile of teeth. Only about a dozen or so, which makes sense: The woman must be in her eighties or nineties.

Vicky straightens up. She lays a finger against the woman’s lower lip and pulls lightly. The exposed gums are drained of color, the toothless ridges unmarred by signs of violence. Like the hair and nails, the teeth have been extracted with great care. She steps back and contemplates the scene. The feeling that she’s overlooked something ratchets up. She takes another step back. A sticky softness tingles against the back of her neck. Swatting at her skin, she pulls long strands of dusty cobwebs away from her body. She flicks her wrist and they sail out into the humid air.

Bugs.

That’s it. That’s what’s missing.

Judging by the condition of the body, this woman has been lying here for several days. The entire room should be a hellscape of corpse-feeding insects. Yet there’s not a single maggot clinging to the lips or nostrils. Not a single fly buzzing around the table.

Vicky backs away. She doesn’t want to lean against the wall, doesn’t want her body to touch any part of this house, but her legs feel weak. The anticipation that strikes her at crime scenes, when she knows just how the images will manifest as she sleeps, is amplified to shrieking levels in this place.

How can there be no maggots, no flies, not even one of those disgusting beetles that actually feed on maggots?

The walls are covered with spiderwebs, but not a single spider. In defiance of all forensics, pathology, and entomology that she is aware of, insects have completely vacated a room where a person lies dead. Vicky pulls off a glove, jabs at her phone, and lifts it to her ear.

“Victoria.” Her partner’s caffeinated voice comes on after half a ring. “You really should be here. You’re missing out. Corner of Stanton and Wheeler, so, you know, the garden district. They got the whole ladies’ auxiliary handing out lemonades.” He pauses. “I’m shitting you, there’s nobody here except the vic. Get this, he caught four in the chest, center mass, like somebody used him for target practice. We’re looking for a real marksman here. You know, I hate when they split us up. But this is what happens when you hit peak summer killing season, we gotta divide and conquer.”

“I need you here, Kenny.”

“Shit, you okay?”

“I need more eyes on this.”

“Weird one?”

“You just have to see it.”

“Ten four, they can roll mine up now anyway. You need anything? Green tea? Granola bar? Methamphetamine in butterfly stamp bags?”

“Don’t stop for any food, please, Kenny.”

“I’m rushing to your side as we speak.”

“I can hear you chewing already.”

“That’s gum. Over and out.”

Vicky kills the call and texts her babysitter: 90% sure it’s going to be a late one. You might be on breakfast duty. So sorry!

Kim hits her back immediately. All good. The peanut’s in bed. We lost George and it was touch and go for a minute, but we discovered him under the radiator in the front hall.

Vicky smiles. George, the stuffed ladybug, her daughter Sadie’s favorite toy, the one she clings to at bedtime. She closes her eyes and imagines Sadie clutching George to the side of her head, claiming it’s the only way she can hear words in ladybug language. Vicky tries to swim inside the memory, but the menthol under her nose fades, the head-spinning ammonia of cat piss rushes in, and she opens her eyes. Her flashlight beam is pointed at the floor, so the corpse on the table is draped in deep shadow.

To live a long life and end up this way, Vicky thinks.

There was once a girlhood, laughter and beach trips, friends and gossip and charm and suitors. If someone could have shown the young version of this woman her sad house and horrible death, what would the girl think? Would it ruin everything, or would she dismiss it with a laugh and a flutter of her hand, something so far off as to be inconsequential? To have no bearing at all upon the girl at the boardwalk linking arms with her best friend and skipping into the wide-open night.

Vicky thinks of Sadie once again, sleeping soundly with George the ladybug. Then she shakes it off and goes outside to wait for her partner.

2

The crickets aren’t supposed to be this loud. Will Bennett’s got the windows of his RAV4 up. Still it’s like a thousand insects are in here with him, crawling over the back seat. There’s no way to drown them out with air-conditioning and music. He can’t turn on the car. He can’t do anything but sit and watch. And listen to the goddamn chirping drone.

He wonders if it’s an upstate thing. If a city boy like him just isn’t used to the noise. Used to it or not, it seems to Will that the good people of Fort Halcott would not stand for it. How could they live like this?

He unwraps another Starburst and trains his binoculars on the warehouse, a low-slung brick of a building with an empty row of loading docks. A single streetlight sends a lonely cone of light down onto the blacktop.

Will’s parked on an embankment in a lot choked with weeds. Thick stems shoot up through cracks in the pavement. Behind him is the empty shell of an old fast-food joint. There are metal speaker boxes on poles for each parking space, the kind of retro 1950s setup where they bring you the food on a tray. Maybe even on roller skates. Fort Halcott’s own Saturday-night malt shop, where the greasers and the preps cruise with their best girls. Or maybe just a Sonic that went out of business.

The warehouse he’s staking out sits empty and silent. Will sweeps the binoculars away from the building. Just down the embankment is the access road that curls through the northeast part of town, where the residential streets give way to office parks and manufacturing centers. Posters on an empty bus shelter advertise last year’s movies. A hubcap sits in a drainage ditch. Cattails sprout from a runoff swamp. He wonders if that’s where all these crickets live.

Will lowers the binoculars. He works the lemon candy around the roof of his mouth. What’s left of it sticks to the back of his front teeth. He should have picked up something else, something with chocolate and peanuts. The motel vending machine had Snickers. He imagines for a moment that he will turn his head and see that the fast-food joint has sprung magically to life. He can smell the cooking oil and grease. Lights shine as bright as a carnival midway. The other cars are long and low, and some of them have fins. A girl glides out on skates to deliver him pristine cheeseburgers and salty fries. She wears a paper hat. Her eyes sparkle in the light. When she gets close to his car, she smiles and his heart stops beating. He knows this girl. She’s been waiting for him. But he can’t roll down his window. Can’t even move. Her smile falters.

THWACK. Knuckles on glass.

Will jolts upright in his seat. He blinks away vestiges of twinkling light. In the rearview the old restaurant is dark.

“Fuckface!” There’s a woman’s voice outside the passenger door. A shadowy figure stands there, radiating impatience.

Will unlocks the car and his ex-wife slides in and shuts the door behind her. Her black leggings and T-shirt are a match for his, more or less.

He fights the urge to lean over and give her a kiss. Old habits. “Hey, Alicia.”

The former Mrs. Alicia Bennett reaches over the console to take the Starburst pack from his lap. “Nice dream?”

“I wasn’t sleeping.”

“Bullshit. There were visible Z’s floating up out of your drooly mouth. It’s not even late, Will. In stakeout time it’s like noon.” She unwraps a little square.

“Don’t eat all the lemon ones.”

“First of all, not a problem, because nobody likes those.”

“I do.”

“Yeah, ’cause your palate is pure old man. Your favorite candy is Werther’s Original. When it’s early-bird-special time at the diner you call an Uber and you’re like, step on it.” She palms a handful of Starburst and flings the pack back into his lap, aiming straight for his crotch. “We should’ve stopped at the 7-Eleven.”

Will grabs his phone and pulls up his photos. He swipes through and stops at the smiling face from his dream. It’s a portrait of a fair-haired woman in her early twenties. She’s posed in business casual against a blank wall. There’s something perfunctory about it. A corporate ID or a college key card shot.

Alicia leans over and affects a deep southern accent. “Violet Carmichael, as I live and breathe, how are you?”

Will makes the photo bounce as he does a posh rich-girl voice in response. “I’ve been positively kidnapped by a freaky sex cult!”

Alicia’s face snaps to all business. She looks at him with those admonishing eyes. “Will. Be serious. This is a life-and-death situation here.”

He takes one more quick look at Violet Carmichael’s eyes and puts the phone to sleep. “You started it, but speaking of life and death, what did you see down there?”

“A warehouse.”

“I knew there was a reason I asked you to come.”

“It’s honestly nondescript as fuck. Words fail me.”

Will pauses. The buzzing cacophony sets his teeth on edge. “You hear those bugs?”

Alicia frowns as she unwraps another candy. “What, the crickets?”

“I can’t believe they’re this loud.”

She shrugs. “Country living.”

“Fort Halcott’s bigger than White Plains. That’s hardly the sticks.”

She gestures out the window at what could generously be called nothingness. “Not exactly Atlantic Avenue either. Plus, there might be a quote-unquote downtown with a few office buildings, but the whole city’s surrounded by the forest preserve. It’s like they stuck Rochester in the middle of a national park or something.”

“We were here the last two nights and I don’t remember them sounding like this.”

“Full moon.”

“That’s your answer for everything.”

“I assure you it is not.”

“It’s always some astrological, Mercury in retrograde—”

“Don’t say always. Nothing is ever always.”

Will falls silent. This is an acknowledged problem for him when he gets worked up. They talked about it in couples therapy with Dr. Capaldi. Will does a quick breathing exercise to center himself. He lifts the binoculars to his eyes for due diligence. Still nothing going on at the warehouse. He lowers the binoculars to his lap and rephrases, working from a place of calm, respect, and clarity.

“It sometimes feels like you use things related to the stars, or astrology, to shut down whatever I’m saying. Like, it’s a way of being dismissive without actually saying, You’re an idiot, I don’t want to talk about this with you anymore.”

“Like when you start to point out aspects of the scenery we’re driving through when I’m trying to engage you in serious discussions you never want to have.”

“Okay, but this is about the specific thing I just tried to bring up, not other hypothetical—”

“They’re not hypothetical—”

“Dr. Capaldi said—”

“Car coming.”

They both go quiet. The car turns out to be a Sprinter van, tall and boxy, heading up the access road from the south. It rounds a long, easy curve. Headlights roam the drainage ditch. The hubcap glints and disappears.

The van hangs a right off the road and heads up the driveway to the warehouse. The fence along the entry glides open on big metal wheels.

“Remote control,” Alicia says. Will agrees, unless there’s someone inside, a guard with a bank of monitors in a security room. She lifts up her night-vision camera with its telephoto lens. “I’m at a weird angle here.”

Will ducks down in his seat. “Better?”

“Can you open the window?”

“It’s like a bug war zone out there.”

“Oh my God.”

“I’ll have to turn on the car to roll down the windows. It might get somebody’s attention.”

Without another word, Alicia opens the passenger door and scampers out to the edge of the embankment. Her body language is pitched at a forward lean, all productive energy and a lack of tolerance for bullshit. He senses a familiar flutter down by the Starburst pack and realizes with a bittersweet pang how much this aspect of her character turns him on. Will figures she left the door open on purpose. It’s a petty move that he also finds arousing.

He keeps an eye on her silhouette and tries to acclimate to the insect noise. The bugs are throwing a rager down in that swamp. He doesn’t know if it’s some kind of mating thing or what. There’s just enough off-key overlap to drive him nuts. It sounds like bugs have crawled inside his head to rub their wings against his brain. He wonders if it really doesn’t bother Alicia or if she just doesn’t want to give him the satisfaction.

Her scent lingers in the car: lavender hair stuff. The insects drone on. He raises the binoculars.

The Sprinter van is parked in one of the loading dock spaces. The dome light goes on inside as the doors open. A man and a woman step out—the driver and passenger. They’re dressed in jeans and T-shirts. The woman slides open the back door of the van and a trio of kids piles out. Not kids, Will corrects himself. Early twenties. Like Violet in the photo her parents supplied. He scans their faces, barely lit by the dome light, and adjusts the focus. Two girls and a guy. He doesn’t think Violet is among them but it’s hard to tell. The woman slides the door shut. The light goes off. He switches to his own night-vision binocs: panoramic quad tubes, PNVGs. The actual view is disappointing. Like every other kid raised on action movies, Will had always expected a certain depth of field from night vision, like the daylight world but greener. The reality is more like tunnel vision with an odd flattening effect. He watches the trio of acolytes from the back of the van carry several large boxes inside the warehouse. Then all is quiet.

Alicia gets in and shuts the door carefully. The volume of the cricket song is barely halved.

“She wasn’t there.”

Will sighs. “Another fun call with the Carmichaels awaits.”

The clients—Violet’s parents—insisted on daily reports. Will bargained them down to every other day. These conference calls are miserable. Will feels like an asshole, finding new ways to wring dubious notes of progress from their methodology. It’s not like he’s lying about anything, it’s just that the realities of this operation don’t lend themselves to exciting updates. This particular cult doesn’t have a single compound where they all live communally and do their composting and perform tantric rituals or whatever. They’re embedded in the fabric of Fort Halcott. They’ve been here for years. Decades, maybe. They own all kinds of property buried in shell corporations. They’re made up of the professional class. Will and Alicia follow leads that aren’t linear. They snake all over town, doubling back, overlapping. Sitting and watching and eating vending machine candy. Their per diem dwindles. And while they’re mired in a web, the Carmichaels grow more impatient by the day.

And these are not people accustomed to waiting around, or to helplessness, or to the feral kind of desperation that the vast swath of non-rich society has learned to weather. That hunger—for decent food, a good job, a full night’s sleep—is an alien feeling to Ed and Fiona Carmichael.

You’re supposed to be the best, Ed is fond of saying in sheer exasperation.

Will wishes he could tell Ed the truth: that he got lucky once. Lucky enough to establish a reputation and burnish it to high heaven.

“Tell them their precious Violet is probably having the time of her life,” Alicia says, “and if they’d been more attentive and understanding, she probably wouldn’t have joined a cult in the wilds of upstate New York. She would have stuck it out in grad school and moved back to the city to help administer her parents’ various philanthropic foundations.”

Will unwraps the last Starburst. “Maybe you can tell them that.”

Alicia twists off the massive lens and cycles through her photos in the viewfinder. She turns the camera so Will can see. Instead of muted green, her photos are a strange combination of sharper imagery and wacky colors: a vibrancy that brings to mind the way the Predator sees.

“New thermal imaging looks good,” Will says with admiration.

“Courtesy of Ed and Fiona.”

Will’s thankful he had the presence of mind to call in his ex in time for Alicia to sweet-talk the client into more cash up front for expenses and equipment. He also has her to thank for their funky hipster motel, the Mountain View Lodge, a comfy tourist trap that beats the hell out of Fort Halcott’s bastions of extended-stay sadness.

Together they cycle through photos while the crickets chirp on and on. The two women are the right age, roughly the same athletic build, but most definitely not Violet.

He closes his eyes. Christ, nothing is easy. In the darkness of his self-pity, the crickets shriek and shriek.

“Will!”

Alicia hits him on the shoulder. His eyes snap open. She points at the warehouse.

A bright flash lights the building from within. Then another. Staccato, off-time bursts that fill the three square windows set high in the wall.

Gunshots. There’s no report from any firearm, but the sound could be dampened by thick warehouse walls. And the hellish chorus of crickets. Will reaches across Alicia’s lap to open the glove box and remove the Sig Sauer pistol.

“Jesus, Will, let it be.”

“No.” He opens the door.

“Violet’s not even in there!”

“We don’t know what’s in there,” he says, stepping out onto the weed-choked blacktop. The day’s humidity hasn’t quite burned away, and he’s instantly coated in a sheen of sweat. Outside, the crickets are percussive, with a deep bass thump to their cries. The noise is incredible.

A moment later, Alicia is at his side, pulling on his arm. “Will, I’m serious.” Her eyes are wide pearlescent circles in the night. “Don’t go in there.”

“I can’t just sit here.”

“You don’t have to prove anything to me!”

He shakes free of her grip. “You think that’s why I do things?”

“Dr. Capaldi says—”

“Fuck off, Alicia.” He starts down the embankment.

“The literary equivalent of swallowing a wasp that’s crawled inside your Coke can. Do yourself a favor and read this book.” – Nick Cutter, author of The Troop

“Creepy, crawly, and endlessly dark, this is Marino’s best novel yet.” – Gabino Iglesias, Bram Stoker award winning author

It begins with cicadas. It will end with the swarm.

When a bizarre murder case lands on the desk of Detective Vicky Paterson, it’s just the start of her nightmare. On the same day, her young daughter, Sadie, is swarmed by cicadas emerging off-cycle from their seventeen-year pattern. Sadie barely survives, and her condition is critical.

Across town, Will and Alicia, two dysfunctional private investigators, are on the trail of a missing girl and the shadowy cult involved in her disappearance. But after the first wave of insects hit, they are forced to barricade themselves in a motel where they must work together with a group of strangers to outlast the invasion.

Soon the infestation is impossible to contain. Humanity rests on the knife’s edge of extinction. And there is a terrible purpose behind the emergence – one that Vicky, Will, Alicia, and a small group of unlikely allies must unravel if they are to survive.

“Marino’s work is unlike any other’s in the genre – horrifying, complex, fascinating, and utterly unique.” – Hannah Whitten, New York Times bestselling author

“Relentless, brutal, and brilliant. An apocalyptic tour de force.” – Craig DiLouie, author of How to Make a Horror Movie and Survive

“Marino has taken the safety of sensations away from me. Every prickle along my arm, the slightest buzz anywhere near my ear – it’s all fodder for nightmares now. Suggesting your skin will crawl after reading this unnerving novel doesn’t come close. Your flesh will fly away.” – Clay McLeod Chapman, author of Ghost Eaters