My first poem, which apparently I composed aloud at the age of two or three, goes like this:

My first poem, which apparently I composed aloud at the age of two or three, goes like this:

There used to be a farm,

There used to be a barn,

Now there is nothing but a big pile of dirt.

I happen to know exactly what mound of ruins I was thinking of when I put that thought together – the pile of dirt is long gone, but the field is still there. I remember being fascinated by ruinous things as a pre-literate child: the boarded up windows of an burnt-out apartment building at the end of our street, a house near the supermarket that was being torn down and whose skeleton walls and staircase were open to the sky, a 1930s trailer that was collapsing in a farmer’s field. I wanted to know who had lived in these places and why they had left and where they had gone. I think that’s why I write historical fiction: to populate the vanished landscape of the past.

I’ve often noticed that modern Europeans feel a greater awareness of World War II than Americans do, and I’m convinced this is because the debris of the war is still all around us here in Europe. Every house on our street in Scotland used to have an iron railing set in a low stone wall in the front garden; every single one of these iron railings was chopped down for scrap iron during the war, leaving a row of metal stubs in the stone. Every town in Scotland has garden walls with iron stubs sticking out of them. Every beach in Scotland is littered with concrete blocks the size of tables, a fortification known as “dragon’s teeth,” which were put there to stop Nazi landing craft from invading the British coastline. I passed through a housing estate on a street named “Beaufighter Way” – the modern bungalows were lined up on a re-purposed World War II runway where a squadron of Beaufighter bombers used to take off and land. Once when I visited a Scottish elementary school, a student told me how he and his family had to call out a bomb disposal unit because they’d found a mine floating in the loch where they were boating while on vacation. The war feels less distant in space to me since I’ve lived in Europe, even as it gets farther and farther away in time.

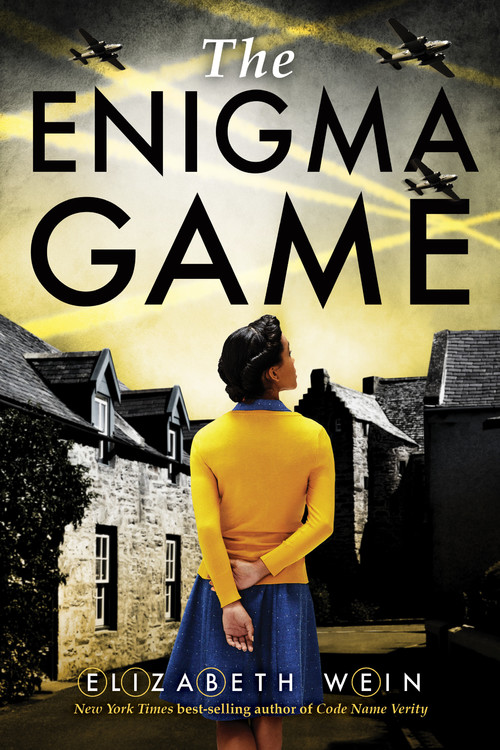

There’s a part of me that desperately wants to understand this stuff, to integrate it with living memory, not just for me, but for my readers, too. And with that in mind, I make up stories that show a world in which people like us lived with these things when they were in use. The Enigma Game, my most recent World War II novel, gets inside the heads of a range of ordinary people – most notably Louisa Adair, a fifteen-year-old heroine of mixed Jamaican and English heritage – but also Ellen, who grew up wandering Scotland as a Traveller; Jamie, a bomber pilot, one of many civilians turned sudden soldier; and Jane, eighty-two years old, interned by the British for being German, a former opera singer and telegraph operator. They’re all based on bits and pieces of me and everyone I know now – life brings them to life in my head and on the page. When I place them in their historical setting, that comes to life for me as well.

READ MORE