It’s Always Been Ours – Excerpt

IT’S ALWAYS BEEN OURS – Chapter Excerpt

My waiting room and office space communicate everything I want patients to know: that my work centers those too often overlooked by my fellow dietitians—Black women, femmes, and queer folks. The bookshelves display covers that address body politics and queerness; the walls are hung with artist Alillia’s life-size paintings of Black bodies, unapologetic in their abundance. My favorite, Breathe Beauty, greets me in the waiting room every time I walk out of my office. The figure in the painting has dark skin with gold highlights around nose and eyes. The figure is naked from the shoulders up, face framed by blue-black, kinky hair falling around the shoulders. Dark, full lips form part of the violet butterfly that is painted around the mouth. The figure’s strong gaze strikes me as empathetic and calm, a welcome presence in an office that holds many emotions.

Mia is in the waiting room, perched on the edge of my couch wearing a pressed navy pencil skirt and a pink silk blouse with pearl buttons. I glance up at Breathe Beauty as I exit my office and greet her. Knee bouncing, Mia’s black spiral-bound notebook is moving up and down on her lap. She has relaxed hair that reaches past her shoulders. It is nine a.m. on a Saturday and, though many of my clients would arrive in casual attire, Mia is dressed to be taken seriously. I am curious about whether she has not been heard or respected by previous clinicians.

As we walk into my office, I turn on the noisemaker for privacy and invite her to have a seat on my black leather loveseat. It’s over- cast in Oakland that morning; she looks out the window as she gets settled.

We exchange pleasantries before I let her know what she can expect from me: honesty, curiosity, and a political context for her experiences. I find that sharing my style up front reduces anxiety for my clients and allows me to connect with them more quickly. One hour is very little time to hear a Black woman’s body story.

Within minutes Mia’s story unfolds. She’s here because she’s exhausted, so exhausted that even a good night’s sleep does not restore her. She’s recently changed medical insurance and met with a new doctor who told her that her lab results show signs of malnutrition, which is how she ended up in my office. Also, at her last salon visit she and her hairdresser realized that her hair is thinning and also has stopped growing. The hairdresser recommended some supplements for hair growth, and Mia is hoping to get my feedback on these, as well as supplements that can fix her deficiencies and increase her energy.

Mia is twenty-four and has just started graduate school in a town close to home. She is in a predominately white aerospace engineer- ing program, the only Black woman in her class. Six months prior to starting her program she embarked on a “Wellness journey” after her previous doctor told her that she was “obese.” That doctor told Mia she needed to lose weight to reduce her risk of developing chronic diseases, ones that she is more likely to get anyhow because she is Black. At twenty-four, apparently Mia needed to be concerned about the ways she is likely to die as a Black woman. Her body, from that appointment on, was a risk factor. Mia hadn’t thought of her body in such a pathologizing way prior to that appointment. Hearing how the doctor problematized her body was disturbing to Mia; she lost the weight he recommended and more. She scoured the internet for advice and looked up ideas for “healthy meal prep.” She stopped eating meals with her family and instead brings over her own containers of food to eat while they share food her mom has prepared. She started going to the gym every day and is now worried to take a day off.

The response to her weight loss has been overwhelmingly positive. She has noticed a shift in her social capital and desirability. Her peers and professors have started looking at and talking to her differently. Her classmates know how much she exercises and praise her for taking the time to do so when the academic workload is so overwhelming they don’t even have time to sleep. Mia appreciates the feedback and interprets this to mean that she is disciplined and Healthy in their eyes. But Mia doesn’t engage with her peers outside of classes because she needs to exercise. She also doesn’t join them for happy hour because she doesn’t want to pay for a side salad—the only thing she eats at restaurants—because she could make the same thing at home for less money. And besides, the alcohol is just extra calories that she doesn’t need.

I ask Mia about her days, and ask more specific questions about how much she is eating and how much she is exercising. I ask her which supplements she is already taking. We discuss what messaging she got about food and bodies as she was growing up. As we continue to talk, she gets visibly impatient. She tells me that she came here for me to tell her what is missing in her diet so that she can take supplements to make up for it, that’s all. I realize that my attempts to build rapport aren’t what’s needed in this moment and decide to be clear about my concerns. I tell Mia that her energy levels will likely improve and her hair may grow back if she begins to eat more food and exercise less.

I see the confusion on her face, the subtle frown line and slightly raised eyebrow. She tells me, “That can’t be the problem; what I’ve been doing is working, it’s getting results. There’s just a vitamin or mineral missing from my diet; maybe magnesium?”

“I understand your concerns,” I share, “but from what you’ve told me I don’t have concerns about your vitamins and minerals, I have concerns about calories, fat, and protein.”

“But I’m the healthiest I’ve even been in my life! I eat intuitively now, my body doesn’t like any of the foods that I used to eat; it pre- fers vegetables and fruit.”

Her body is no longer a risk factor.

When I ask Mia if anyone has expressed concerns about her food restriction and rigidity, she assures me this isn’t what’s going on here—it’s not about weight loss or the thin ideal; it’s about her health and feeling good in her body. I ask whether people have talked subtly about her food, and she tells me that her sister has noticed what is going on and offered to support her. But Mia doesn’t need support; she just needs me to tell her how to fix the problem so that she can get her energy back and thicken her hair.

I hear this regularly. It’s not about dieting. It’s about “Health” and “Wellness.” It’s about feeling “clean.” And because this pursuit of Wellness also feels like a pursuit of purity and morality, she is happy to perform whatever rituals or sacrifices may seem necessary to contain her body.

I explain to her how energy deficits impact the body and why this would explain her experiences and lab results. She listens, opens her mouth to say something, and then pauses. She looks out the window and becomes tearful. “I can’t be the only Black person in my class and also be fat,” she says. And there it is, the reason why Mia is here: the impacts of white supremacy on the body narratives of Black women and the safety found in conforming to what whiteness demands.

All I can do is nod.

Black women are tasked with existing in a society that views us as disposable.

The politics and constructs that shape society shape our bodies. White supremacist capitalism objectifies and commodifies individuals. It creates social hierarchies and then makes money by selling us the promises of thinness, Health, and, ultimately, whiteness.

Mia and I discuss the impacts of white supremacy on the desirability of Black women. I let her know, without judgment, that I understand how conforming to what whiteness demands makes us more palatable in predominantly white settings. We discuss how straightening our hair, restraining ourselves, taking up less space—both figuratively and literally—and even lightening our skin can make it easier to get a job, a partner, and a home loan. We discuss how we have survived living in a world that doesn’t value Black women by negotiating physical and psychological stress and trauma daily.

I tell Mia that I often see marginalized people engage in practices that can negatively impact their well-being in order to lessen microaggressions, organize their day-to-day actions, and strategize existence. Navigating a competitive, predominantly white graduate program is hard enough. Mia tells me she fears that if her body conforms to the stereotypes of Blackness that her classmates have, she may finish the program but won’t have the networks she’ll need to advance in her career. In Mia’s mind, becoming thin is not about being a certain dress size; it is about survival. If others perceive her body to be a disciplined body, she knows she will be treated with more respect by classmates and professors.

I share that I know she began her Wellness journey with the best of intentions. And that I understand how the positive feedback and attention she’s getting for having lost weight make it easier to navigate everyday life.

Mia is quiet. I am quiet, too. I want her to take her time. After a minute or two, her feelings bubble up.

She wipes a tear from her cheek and tells me that, though she may agree with me in theory and understands that eating food may give her more energy, she just can’t gain weight—it’s too much of a risk. In fact, she would like to lose more weight “to be safe.”

I know.

Our safety is contingent on how little of a threat we pose to those around us. If we can make ourselves smaller both literally and figuratively, we may be able to uncouple ourselves from the savagery associated with our Blackness.

Our humanity is tied to how well we can conform to what whiteness demands. We might swallow parts of ourselves, rather than food, to become more palatable to others. We may hold ourselves and other Black women to higher standards than we would any other group of people. We seek respect, and get tripped up in respectability. Our survival in society directly correlates with our resilience. We push ourselves beyond capacity to get through our day-to-day tasks.

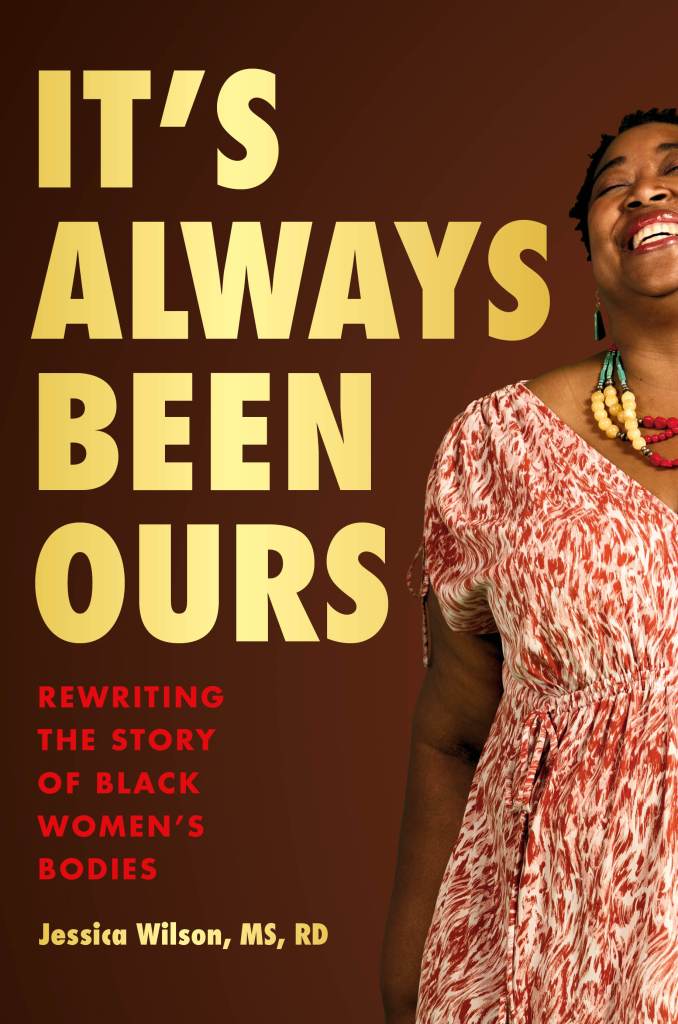

This book is about bodies and how Black women are told to have them.

The dominant narratives about all bodies were crafted centuries ago and continue to be told today. From birth, our body sets expectations for those around us. This book makes the case for rewriting those narratives, for putting Black women at the center of the narratives, rather than having our stories filtered through a white lens. I use the body as a vehicle with which we can conceptualize how these stories have shaped our lives and how we might rewrite them going forward. I use the body as the vehicle for storytelling because, as Isabel Wilkerson puts it in her book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, it is a flashcard by which we are viewed and judged in our society. It signals race, gender presentation, visible ability, age, size and shape, and class. Wilkerson notes of the race-based caste system in the United States: It’s “an artificial construction, a fixed and embedded ranking of human value that sets the presumed supremacy of one group against the presumed inferiority of other groups.” She provides a global view of the ways in which caste has shaped this country and a complex argument for the ways in which Blackness and whiteness have been artificially constructed. She argues our bodies signal “traits that would be neutral in the abstract but are ascribed life-and-death meaning in a hierarchy favoring the dominant caste whose forebears designed it.”

Noting the fluidity of race and the shifting requirements for those assigned whiteness, Wilkerson says, “Race is what we can see, the physical traits that have been given arbitrary meaning and become shorthand for who a person is. Caste is the powerful infrastructure that holds each group in its place.”

The caste system exists because of the racial distinctions between bodies, and I argue it lives on in our bodies. It relies on the meaning and narratives we assign to bodies. This meaning impacts the ways in which society celebrates, tends, penalizes, and pathologizes people in the United States and other Western and colonized countries. Our bodies are pivotal in the assignment of power and privilege.

I use caste rather than race when referencing the impacts of white supremacy. Caste is governing, while racism is often attributed to personal bias. Books, TED Talks, articles, and corporate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) presentations provide audiences with the simple one-to-one solutions to bias. Racism is positioned as both a conditioning and a failing of the individual. The complexities of race are simplified to how we feel and what we think about one another. We’re told that we’re relying on stereotypes and “making assumptions” when perpetuating anti-Blackness. Race is regularly pitched as an interpersonal concern rather than a struc- tural one, which makes the case that we can unlearn race. Even if individuals unlearn the set of rules assigned to skin color, unless something changes, we will still all be bound by the systems of caste in society.

I come to this book with both marginalized identities and privilege. I am a queer, Black woman, with an uncontrolled seizure disorder, all of which impact my experience and interactions in this world. I am also mixed race, with looser-textured hair, which makes me more palatable as a Black woman. I have an advanced degree, and my profession offers me a livable wage. I am thin. Though I will speak about a variety of lived experiences, I am only an expert of my own and bound to make mistakes when speaking about the experiences of others.

This book talks a lot about fatness as well as Blackness. Even though I experience “the residue of anti-fatness,” as Bryan Guffey puts it in an episode of the podcast Unsolicited: Fatties Talk Back, I do not experience the violence directly, and as such, readers will benefit from seeking out the writings of others and learning directly from their experiences as well.

You’ll see a lot of me in this book. Much of its content has come from my experiences as a dietitian who remains both hypervisible and erased in my profession. I am one of the 3 percent of Black dietitians who make up the field. In my coursework I was “taught” about Black people and what “they” eat and what to tell “them” about nutrition. Similar to Mia, I was taught that the bodies of Black people are inherent risk factors just for existing. In my training decades ago and at conferences into the 2020s, I have heard about Black people’s individual responsibility to take three buses to get to a grocery store to buy whole grains and leafy greens: quinoa and kale. Southern food is constantly vilified by dietitians and directly associated with Black people at the same time hipsters and gentrifiers are enjoying a renaissance of ribs, pork belly, greens, okra, mac and cheese, chicken and waffles, and cornbread. When the same foods that are pathologized in the context of Blackness are associated with thin, white, affluent people, they become a foodie’s gastronomical paradise. Bay Area residents can enjoy a lemon-lime Alameda Point craft soda with their BBQ pork riblets from Jupiter, a brewhouse in Berkeley, all while shaming and taxing those who buy Sprite from the corner store.

For the majority of my career, I have worked with people who have restricted their food and/or have tried to shrink and contain their body in some form or another. I have been the only person of color in a room full of eating disorder clinicians more times than I can count. Eating disorder conferences are a sea of thin white women with straight hair falling just below their shoulders. Multiple times I have been approached by conference attendees who call me by some other name because they think I’m the one Black clinician they know. I am often the peppercorn in their saltshaker; I am only there via accident, but once I’ve settled in, I’m hard to remove. I somehow always end up in the corner, visible and obviously out of place. The eating disorder field has never been ready for me and the truths I tell when I show up. Similarly, it has never been able to support my clients. Centering those most impacted by the narratives written by white supremacy was, and continues to be, too great an ask for a field that prioritizes those who have been written to be fragile and vulnerable: thin, white, cis women.

I come to this book as an expert only of my own clinical experiences rather than an expert of evidence-based practices. In part, because I just can’t. As of this writing, when I look in the National Library of Medicine database, also known as PubMed, and type in “eating disorders” and “Black women,” only ten results from the last five years appear, and only one study of Black women exclusively, while the majority compare Black women to white women, who are clearly defined as the norm or default sample population. Meanwhile, there are 8,173 results for “eating disorders.” I don’t think it is ethical to say that we’re providing “evidence-based” care to Black women with eating disorders when they are present in 0.001 percent of the research.

I also won’t cite many peer-reviewed sources because the re- search areas and hypotheses are biased. For example, of those ten results for Black women, there were three for binge eating disorder, three for bulimia, and zero for anorexia; the other four were not specific to eating disorders in Black women. The focus on eating disorders that involve a bingeing component is consistent with this country’s association of Blackness with gluttony. Researchers and institutions erase Black women from studies that don’t fit with societal expectations for our bodies. So often in our society, if something hasn’t been “studied,” it doesn’t exist. As such, one could make the argument that Black women simply don’t get anorexia. When people are not assessed and diagnosed with restrictive eating disorders, they are more likely to have adverse outcomes, and it can require far more resources to support someone’s recovery than had they been supported earlier. I’ve endured multiple eating disorder educational events during which clinicians, including Black clinicians, stick strictly to the research without critiquing the biases and discrepancies in the data collection and the results. This not only reinforces the idea that Black women only have eating disorders with an “overeating” component but also results in Black clinicians inadvertently pathologizing themselves and reinforcing their connection to gluttony.

In 2021, I was excited to attend a webinar about eating disorders among Black women in college settings hosted by two Black psychologists and eating disorder “specialists.” Finally, someone was talking about the population I was most interested in! The clinicians, both of whom worked for a college counseling center, told the audience that they have observed emotional and binge eating in Black female college students, consistent with the existing research. The clinicians believe that Black women are more likely to binge eat coming to college, compared to white peers, because they witness Black men dating white women in college, specifically. They hypothesized that this leads to emotional eating from their despair. The clinicians even showed us a photo of what seemed to be a formal fraternity event with a group of Black men paired with white women. This was supposed proof of their hypothesis and how they were able to align with the academic research.

Girl, no. This reductive explanation for the presence of disordered eating in Black college-aged women is not what anyone needs. Making these conclusions not only reduces the causes of disordered eating to desiring the attention of a man but also centers men in stories about Black women’s bodies. This message ignores the entire story written about Black women’s bodies by white supremacy. Good thing this webinar was free. My heart was broken thinking that these were the messages the presenters were sharing with their clients and that students would contextualize their experiences such that attention from Black men would be a recovery goal. I was simultaneously disappointed that this was what the au- dience would think was true about the experiences of Black women with eating disorders. I couldn’t help but also wonder what these clinicians thought of their own body stories, and how much of their self-worth was in the hands of Black men. Black women are not immune to taking on the narratives about our bodies that we have been told for decades.

This presentation was one example of our society’s overreliance on data and “proof ” to justify someone’s existence. In clinical care, so often we do not allow individuals to be the experts of their own experience and to tell us what they need. Most nutrition, body weight, and Health-related data do not examine the intersections of race, socioeconomic status, trauma history, gender identity, sexuality, disability, neurodiversity, documentation status, and access to food, safe drinking water, clean air, education, employment, health care, and transportation—among many other disparities. When we consistently center thin, white, cis, non-disabled, neurotypical, and well-resourced people in our “best practices,” there is no way for us to ethically incorporate “evidence” into our work, in my opinion, with people who do not have these privileged identities. Instead of best practices created to be inherently exclusionary, I will use the narratives of those around me, my clients, my friends, my family, and my colleagues, to illustrate the outcomes of body stories written through a white lens. The long-standing narratives written about Black women’s bodies shape how we all navigate the world. Black women in Western society were denied the power to write our own existence into national and international discourse, and try as we might, the lens through which we view ourselves and other Black women is invariably shaped by what whiteness has demanded.

This book examines the ways in which this shows up in ourselves, in our relationships, and on our bodies. I explore the ways in which the structures and systems that govern our lives are heavily based on the stories written, by white supremacy, about our bodies. I explore and critique the contemporary solutions to the negative messages we receive about our bodies, and I make the case for a shift in how we write and read body narratives.

In my training to become a dietitian, I didn’t learn about the structural forces, epigenetics, or toxic stress that impact the food eaten in marginalized communities. As dietitians, we’re educated to believe in individual responsibility; we’re taught to tell our patients to “eat healthier” and that the only barrier to doing so is their willingness. Trauma is not discussed, and dietitians are not taught how to hold the trauma for our clients.

I was taught that eating disorder treatment was best left to therapists. Dietitians could provide specific meal plans, but most of the work would happen in therapy. I didn’t learn how to become an integrated member of a treatment team that includes therapy and medical and psychiatric support until I was already doing the work. Dietitians were taught the medical impacts of starving and purging via vomiting, that was it. It formed how I viewed eating disorder behaviors to have one of two presentations rather than a wide spectrum with many intersections. As training was limited, it was easy to adopt the common perception in the field that all women adopt disordered eating patterns for a sense of control and a desire for thinness, visibility, status, and the male gaze. As such, the conversation includes gay men, who are also assumed to value the male gaze. All other individuals are routinely disregarded. Eating disorders in Black women and other folks whose bodies don’t conform to societal requirements are often different—and more harmful—quests. White women, by virtue of being white, are closer to this culture’s racist body ideal, and therefore closer to feeling safe and seen, even as they may also hold marginalized identities. Black women will never come close to the body ideal that whiteness upholds—thin will never be thin enough to tame a Black woman’s body.

This harm not only validates disordered eating for Black women but also leads to internalized anti-Blackness and shame.

I am constantly focused on how to care for bodies that are stereotyped as strong but that are, in reality, deeply vulnerable to the manifestations of white supremacy. In my practice, I help my patients contextualize how the narratives written during enslavement continue to exist today. Black women often take on the false idea that we have superhuman strength and resilience, in the meantime sacrificing our physical and mental health trying to make ourselves fit into a society that will never accept us. This replicates centuries of lacking body autonomy for Black women, of being denied agency in how we tend to our bodies.

Early in my learning I would have approached Mia from a place of already knowing. I would have told her she needed to talk to her doctor about getting an eating disorder assessment. I would have created a meal plan for her and a goal of trusting her body and eating intuitively.

But today I don’t. Instead, I listen.

We discuss the influences of whiteness on her reality, and I validate her experiences. I tell her I don’t have The Answer because her experience is rooted in both her lived experience and the politics of the external world.

She isn’t ready to hear about this. She isn’t ready to give things up. And that’s okay.

A glance at the clock tells me our time is almost up, and I offer Mia a follow-up appointment. As she disappears down the hallway, I lean back against the wall and look again at Breathe Beauty. I let out a deep sigh and invite air down into my belly after holding it tightly in my chest. These moments never get easier. After appointments like these there’s a mixture of sadness, anger, and despair that swirls within me. The first few times it happened, I teared up, at a loss for how to problem solve something with clients that was impossible to fix; fixing was something I’d been trained to do. I’d sit in silence as clients shared their trauma, knowing I couldn’t change anything about the past, and wonder what my role was in these situations. I couldn’t share my experiences with white colleagues in consultation because no one was experiencing what was in the room with me. The realities of living under white supremacy never get easier, but over time I’ve found ways to channel my energy into collective and cultural change. In 2020, I finally found other Black clinicians who did similar work and experienced the same dynamics in their office. And having clients trust me with their stories and allow me to offer support on their path to healing is my healing as well.

In writing this book I endeavor to make my language as clear as possible, and when writing about identities that aren’t my own, I defer to thought leaders and community members to guide me.

I use white supremacy to describe the ideology that created the race-based caste system that prioritizes and protects white people and serves to destroy and demoralize all others. And I use the term whiteness, not as the white race but as the ways white supremacy shows up in our society and on our bodies. In this book I note the many ways whiteness is working the way it is intended. An example of it working is when white people, especially white women, take cultural criticism personally; they make it about them rather than about the structures of caste. Taking it personally distracts from the systems that uphold whiteness and lets people focus on one-to-one relationships and individual solutions to systemic problems. It means they never need to be uncomfortable with complicity and complacency under white supremacy. To describe body size and shape, I use thin and fat. Although both terms are social constructions, fluid and situational—think “fitness,” entertainment, cities, regions, communities—in this book I use these distinctions as a function of access. I use thin to describe people who are generally able to go shopping for clothes and find something that fits them without needing to seek out a specialty store or a different section all the way in the back. Thin people don’t need seat belt extenders on airplanes and in cars and don’t have to think twice about whether they can find seating wide enough and with a high enough weight capacity to hold them. In this book thinness has nothing to do with body weight because the appearance of someone’s body size is how we are judged by society. I use fat to describe people who are told their sizes are only available online or who are unable to get clothing items from independent suppliers because having them in stock “would drive up costs on all of our merchandise.” Fat students aren’t able to sit in the lecture hall seating of the universities they pay to attend. Fat people are denied medical care because society abides by arbitrary cutoffs in sizes and weights for certain medical equipment like blood pressure cuffs and procedures like surgeries. Fat people who can become pregnant aren’t often told that emergency contraception, other than a copper IUD, isn’t as effective for them. Fat people are often preexisting symptoms in and of themselves and are denied humanity in the medical system.

Fatness is often interpreted as a moral failing, a Bad Thing. Fat activists have reclaimed fat as an adjective. Ashleigh Shackelford states, “Fat is a descriptor in the same way that black and queer are descriptors. And fat is somewhat similar to black and queer in more than just that way; it’s also a word that encompasses a marginalized identity. Yes, fat is a neutral and descriptive word, but when it’s an identity, it’s much more than that. To reclaim this word, or any word, is to lean into an identity as a form of revolution against fat phobia, racism, and so much more. For me, fat is a way of saying ‘f*ck you.’”

When referring to body weight designations, as applied by the World Health Organization and the medical-industrial complex, I use quotation marks because “underweight,” “normal weight,” “overweight,” and “obese” are assessed by height and weight equations and do not always align with the size of our bodies. For example, “obese” people may not be fat. They also pathologize body weight, body size, and therefore people who are any measure above or below the realm of what is deemed “normal.” These words are used only in the context of the medical-industrial complex.

I use both Health and Healthy, and health and healthy. I use Health and Healthy (capital H) as states of being and to describe the broader social agreements in the United States of what makes a good body. Health (capital H) is a social construction and often assumed via body type alone. Lowercase health and healthy are the medical textbook definitions, the absence of disease; healthy people go to the doctor and are told they’re fine.

I use Sick as an identifier for those of us with chronic illnesses, those with a medical diagnosis, those who have yet to be diagnosed, and those for whom there isn’t a medical diagnosis to encapsulate their experience of illness under white supremacy. I use Sick as an identity, a state of being. I will use sick (lowercase s) to describe a general or acute illness and in the context of the medical-industrial complex. I use Wellness (capital W) to describe the billion-dollar industry that promises a transcendental experience of a body and the purity and morality associated with the engagement of Wellness practices. Instead of a lowercase wellness, I use well-being because it refers to a state of existence.

I use the term marginalized in this book. At the time of this writ- ing some activists and educators are shifting from using marginalized to terms like historically excluded and intentionally ignored. I want to acknowledge this shift away and note that I have yet to find a term that I believe represents the contemporary violence of what people continue to experience in a society that has been constructed in such a way that anyone who falls outside of what whiteness requires will never be allowed to fully participate, even if they were to be included.

When I use Black women, I mean every Black woman, all sexes assigned at birth. The experiences here center Black women and you will find they may be applicable to many people whose body stories have been written by whiteness.

In my discussion of race, specifically for Brown and non-Black people of color, I am not referring to those who are assigned white- ness or who are considered to be white passing. Although I understand that people may choose to identify as a person of color, consistent with their ethnicity, family, heritage, and political identity, I refer to race as an assignment. I understand that race is a social construct and fluid, as US history has shown, so I am not referring to people who are protected and shielded by their ability to be seen as white. For the purposes of this book, those who are assigned whiteness are a part of the dominant caste. They may share cultural experiences with Black and Brown people, but they do not carry the same flashcard of how they are to be treated, and thus have different experiences navigating the structure and systems that organize the existence of the colonized country that is called the United States.

Most of this book takes place around 2020–2021. It was a time during which Black women were noticed, perhaps in ways we never will be again. And even then, our Blackness was viewed through the lens of whiteness. In 2020, people were discussing the need for Black women to lead. There was an increase in anti-racism training and internal DEI promotions were suddenly trendy. Our focus was drawn to the new bright shiny object, the solution. “Learning” was pitched as The Way to getting out of a caste system, yet came with no expectation of “doing.” Meanwhile, those of us who need justice and liberation are expected to witness white people, and those with close proximity to whiteness learn about their privilege. We’re expected to take a wait and see approach to whether this “learning” ever translates to doing.

Nationally, white author Robin DiAngelo’s book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism was fast becoming a best seller. White fragility, as a concept, is convenient; it provides a reason for people to excuse themselves from hard conversations and not have to sit with discomfort. When we label someone’s defensiveness and lack of willingness to sit with discomfort as fragility, we distance them from the harm they have caused. We attribute the harm to their whiteness rather than their lack of ability to do better, be accountable, or simply be a decent human being. White fragility, as a concept, upholds the belief that whiteness is delicate, frail, and needs protection. It perpetuates the idea that Blackness, inherently the opposite, is strong, resilient, and won’t experience pain.

The stories written about all bodies, from their race and shade to their size and shape, from what they should eat to how to do so, have historically been written by medical doctors, researchers, professors, and religious leaders. For centuries, white men with some version of credentials and, increasingly, white women with the same have been those who have constructed the narrative of a “good body.” This group of people has dictated which bodies follow the rules and, consequently, which do not. It constructed the parameters for bodies that uphold the historically Anglo-Saxon values of purity and morality at the foundations of many Western societies. The pure, moral, rule-abiding body has never, ever been a Black woman’s. The narratives about Black women’s bodies are always juxtaposed with those of a better body, historically a white woman’s body. Fast-forward to the end of the twentieth century and then a quarter into the twenty-first, and white women are dominating the narrative about Health, Wellness, and body positivity. These constructs are no accident; they are by design.

This book makes the case for a cultural rewriting, something that does not fall directly upon the shoulders of those most impacted by our current system of caste but on a society as a whole. In their book Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness, Da’Shaun L. Harrison notes that “systems and institutions are maintained by power but are created first through an idea. At the root, liberation must mean cultural revolution as well as a deconstruction of the sociopolitical institutions that hold these systems in place.” Everyone needs to participate in this revolution. This book makes the case for a cultural revolution that centers and prioritizes Black women, those who have been most impacted by the patriarchal, capitalistic, caste-based society in the United States. The ideas about Black women and our caste system need to change.

This book is specifically for Black women. To end the pathologizing and problematizing of our bodies, for us to stop placing ownership of whiteness onto our bodies. May you see yourself in a book about bodies in a way that hasn’t been done before. May you see that none of it has been your fault. It’s been by design. The world was not constructed to take in your abundance.

Having a body is hard. Hopefully, the conversations you find here will help you make sense of your experience in a way that lets you live a bit freer.

This book makes the case for a new narrative and demands that we all celebrate Black Joy.