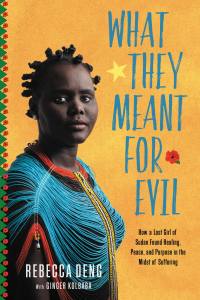

Rebecca Deng’s What They Meant For Evil Illustrates Faith and Survival With an Untold Story

“I am one of the Lost Girls of Sudan. I am not the first or last Lost Girl.”

This is how Rebecca Deng identifies herself in the first few pages of her memoir, before she begins to put into words an impressive record of what is was like as a girl in a time of immense conflict.

The Second Sudanese Civil War was a brutal, ruthless war that lasted twenty-two years. It involved child soldiers, slavery, mass killings, and the death of two million people—a situation so dire that it can be hard to conceptualize. For Rebecca Deng, the war wasn’t some abstract idea. It was reality, a traumatic reality that displaced her from her home and led her to become one of the Lost Girls of Sudan. These girls were only 89 of the 4,000 Sudanese refugees approved to settle in the United States, where Deng lives happily with her husband and children.

Though other writers have penned stories about this war (for example, Nathaniel Chol Nyok’s heartbreaking Days of Refugee: One of the World’s Known Lost Boys of Sudan), they have mostly centered the Lost Boys, not the Lost Girls, who experienced the same war under different circumstances due to their gender. The Lost Girls’ narratives were greatly ignored compared to those of their male counterparts, but now, thanks to Deng, some light can be shed on their experiences and often-forgotten perspectives on this conflict. Deng’s What They Meant For Evil is a harrowing, poignant account of the traumatic events that occurred during her childhood and adolescence, beginning with an attack on her village during her youth.

Deng recalls the land of her youth with whimsical, often colorful language, showing the reader just how beautiful her village was before violence changed it entirely. Though the uplifting, carefree prose describing pre-war life soon vanishes, she still writes with the spirited innocence of a young girl, which only drives home the heartbreaking reality she had to face.

The story itself is, dare I say, Biblical in proportion. With its wild tales of pythons, crocodiles, enemy soldiers, and other near-death experiences, What They Meant for Evil feels like a Biblical tale where the hero suffers through many ordeals but always retains her faith. Weaving Biblical quotes, maxims, and stories into her writing, Deng makes clear the role that spirituality and faith has had in her processing and moving forward after immense trauma.

What They Meant for Evil continues after Deng comes to the United States as a refugee. There, she must cope with a brand new way of life, culture, and expectations. In addition, the memories of her past are not easy to move beyond. Struggling to make sense of what she went through, Deng reveals that faith in God allowed her to claim her scars (physical and emotional) as symbols of strength and perseverance. Though faith-oriented readers may find particularly meaningful lessons from Deng's story, its central themes of hope, love, and survival after trauma are sure to resonate with anyone, regardless of religious affiliation.

As one of only 89 female refugees admitted to the United States, Rebecca Deng and her story deserve widespread recognition. What They Meant for Evil is a matter of historical importance, not just a record of individual catharsis. Deng writes that originally, she didn’t want to painfully relive her experiences for an outside audience. But after coming across a museum exhibit detailing how some Native American women would write down the stories of their lives and never share them, she felt compelled to speak. She needed to share her journey so that her own children would know their historical legacy, but also so that all those girls who could not speak would now have a voice.

Our spiritual beliefs and practices are deeply personal, but there exist rare stories that speak universally to the power of faith and its role in surviving the unthinkable. Rebecca Deng’s What They Meant for Evil is one of these.

About Rebecca Deng

Rebecca Deng, of South Sudan’s Dinka tribe, is one of the 89 Lost Girls who came to the United States in 2000 as a refugee after living for eight years in Kakuma Refugee Camp in northern Kenya. The violence she experienced as a child during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005) has given her a deep empathy for children and young adults who face similar situations today. Today Rebecca is an international speaker and advocate for women and children who have been traumatized and victimized by war. She has spoken at the United Nations and served as a Refugee Congress delegate at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Washington, D.C.

What to Read Next

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Mya is a poet and writer in New York City who lives with their kitten, Ramen. You can find them and their work @literallymya on Twitter.