Waco Revisited

It is hell. Day and night booming speakers blast us with wild sounds—blaring sirens, shrieking seagulls, howling coyotes, wailing bagpipes, crying babies, the screams of strangled rabbits, crowing roosters, buzzing dental drills, off-the-hook telephone signals. The cacophony of speeding trains and hovering helicopters alternates with amplified recordings of Christmas carols, Islamic prayer calls, Buddhist chants, and repeated renderings of whiny Alice Cooper and Nancy Sinatra’s pounding, clunky lyric, “These Boots Were Made for Walking.” Through the night the glare of brilliant stadium lights turns our property into a giant fishbowl. The young children and babies in our care, most under eight years old, are terrified.

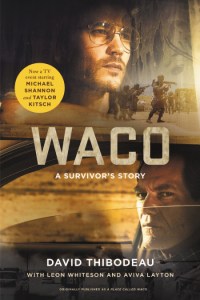

This is the opening paragraph of former ‘Branch Davidian,’ David Thibodeau’s memoir, WACO: A Survivor’s Story—an insider’s account of one of the most disturbing and tragic episodes in modern American history, and the source material for Paramount Network’s new miniseries of the same name.

WACO, both the book and the series, has two audiences. In one category sit those who remember it first-hand, those who watched in 1993 with a worldwide audience as the federal government faced off with a holed-up cult on 24-hour cable news. In another are those who, like myself, were too young to remember Waco, for whom the events in rural Texas truly are history. Now on the 25th anniversary of the siege, no matter which category you fall into, Thibodeau’s story offers an unprecedentedly vivid, raw, and detailed portrayal that does what no news cameras could do: go directly into the inferno.

WACO is a page-turning memoir that reads like a thriller. We might all know (or, at least, have a vague sense of) what is coming, but the ever-ramping tension that carries Thibodeau’s narrative towards the final climax is never anything short of riveting, providing a unique perspective on the details we do know, and offering insights into what news cameras could ever see. Most surprising to me was Thibodeau’s characterization of David Koresh, the messianic leader of the Waco cult. Although the mysterious, charismatic, delusional figure is certainly shown to have a dark side in Thibodeau’s telling, Koresh is also presented in a benign light, as an occasionally humorous and charismatic leader with a passion for the guitar.

Indeed, it was through music, we learn, that Thibodeau and Koresh met: one fateful night at a local venue, Koresh’s cover band found themselves short of a drummer but discovered a replacement in Thibodeau. And no sooner was Thibodeau drawn into Koresh’s world at the Mount Carmel compound, a world where Branch Davidians lived together and studied scripture, where drinking and smoking were prohibited, where men were expected to remain celibate and give their wives up to Koresh if he so requested. It is narrative tidbits like this that Paramount Network producers John Erick and Drew Dowdle draw out in their six-episode miniseries, which adroitly transposes Thibodeau’s intimate story into compelling visual form.

25 years later, WACO offers a complex portrait of an enigmatic, contentious event that, even to this day, defies attempts to cleanly distinguish what happened into right and wrong. Thibodeau’s memoir and the miniseries cover a lot of ground—cults, religion, guns, police brutality, and the scenarios that cause tension between the government and its citizens to escalate. That much of this feels pertinent in our present times makes WACO vital reading in 2018, whether you bore witness to the event as it happened on the news in 1993 or, like me, if you are experiencing it now a generation later.