The Millicent Quibb School of Etiquette for Young Ladies of Mad Science | Chapter 1 Sneak Peek

October is a long time to wait to get your paws—I mean hands—on a copy of Kate McKinnon’s wacky, hilarious The Millicent Quibb School of Etiquette for Young Ladies of Mad Science. BUT, because we are the absolute best, we’re giving you an extra special sneak peek, and have revealed chapter one early!

CHAPTER 1

THE INVITATION

THE MYSTERIOUS INVITATIONS appeared on a Tuesday.

They appeared inside three backpacks belonging to three pupils at Mrs. Wintermacher’s School of Etiquette for Girls in the town of Antiquarium. 1

No one saw who might have put them in the backpacks, because the backpacks were kept all day in the backpack room, and that afternoon the students were busy in the demonstration room. What were they doing in the demonstration room? They were watching a demonstration. Keep up!

Mrs. Wintermacher, the proprietress of the school, was demonstrating how to sit on a velvet fainting couch.

“Let us begin,” she said. “Sitting is, as you know, the delicate art of not standing. In Antiquarium, if you attempt to sit without the proper training, you may be wounded, or worse, look weird.”

She pursed her gray lips, struggling to balance all the exotic feathers and fruits and taxidermied animals that adorned the brim of her enormous hat.

“Today we tackle the hardest couch of all: the velvet fainting couch.”

“Oooooh!” gasped the pupils.

Yes, velvet is a cruel mistress. “There are no fewer than eighty-five different poses that you must memorize for this couch. We’ll begin with the simplest, which is ‘Upright Sit with Straight Back,’ and gradually we’ll work our way up to more difficult maneuvers, such as ‘Fainting During Public Waltz’ and ‘Laughing at the Admiral’s Joke.’ I’ll begin.”

Mrs. Wintermacher sat straight as a sword on the velvet couch while all the pupils watched with rapt attention.

Well, not all. Not…

Look closely at them, please. Memorize their names and attributes. They are the heroes of the book, and their names will be invoked constantly. If you don’t know them, things will quickly descend into chaos.

Gertrude. Eugenia. Dee-Dee.

These three gnarly nerds did not belong at Mrs. Wintermacher’s School of Etiquette; nor did they belong with their fake aunt and uncle Parquette, who had adopted them as infants; nor did they belong in the pristine town of Antiquarium; nor even did they belong in the year 1911— which is a shame because, try as one might, one cannot change the year.

Though they were not technically, biologically, sisters, Mrs. Wintermacher hated them all equally. This was because they were all equally disinterested in etiquette, instead preferring various scientific pursuits. Eugenia liked explosions and searching for expensive rocks. Dee-Dee liked building machines. And Gertrude was interested in things like bugs and beetles and what makes the purple feathers on pigeons sparkle and what makes soap bubbles have rainbows in them and where does a newt lay eggs and do cat whiskers feel anything and are guinea pigs related to pigs and how is a chili pepper hot and things like that.

So instead of paying attention during lessons such as “Proper Pinky Angles for Picking Up Teacups” and “History of Soup Spoons,” the Porches were usually huddled in a corner, absorbed in something else.

For instance, at that moment, Eugenia was chipping away at a rock to see if it contained diamonds, Dee-Dee was adjusting the spring tension on a miniature catapult she’d built, and Gertrude was petting the live bat that she’d stashed in her pocket.

“Dee-Dee, that catapult rules!” Gertrude whispered. “What’s it for?” (Gertrude, it should be noted, had a tall dome of black hair cut bluntly beneath her ears.)

“You know what they say: A catapult never reveals its destiny until the time is right,” Dee-Dee said. (Dee- Dee, one should know, combed her tight curls into two dandelion-esque poofs on either side of her head.)

“Can you use it to fling me out of here?” Eugenia grumbled. “I can feel the dust settling on my brain from disuse.” (Eugenia, it must be said, bundled her mane of wavy brown hair into a nest that pointed far behind her, as if to say, “Stand back.”)

Gertrude smiled at her sisters. “Too true, Eugenius.”

“Now!” Mrs. Wintermacher barked. “Who would like to demonstrate for the class?” Her gentlest smile looked like the frozen scream of the stuffed weasel that leered over the brim of her hat.

She looked out over the faces of her perfect pupils, who were all eagerly raising their pinkies, hoping to be called upon: Imogen Crant the glue heiress; Ellabelle Belle- Parker the ballerina; Posey Picard, whose cheeks were the inspiration for a line of under-eye creams for adolescent girls; and of course, the Porches’ seven cousins, who were all perfect, and who were all named Lavinia: Lavinia-Anne, Lavinia-Vanessa, Lavinia-Jennifer, Lavinia, Lavinia-Lavinia, Lavinia-Gwyndoline, and the youngest, Lavinia-Steve—whose debilitating allergies made her just one degree closer to the human experience.

Mrs. Wintermacher’s gaze drifted past all their dainty pinkies and settled instead…in the corner.

“Miss Gertrude Porch,” she said. “Please demonstrate.”

If you’ll remember, Gertrude was busy petting the bat in her pocket—so much so that she didn’t hear Mrs. Wintermacher say her name.

“Are you hungry, my good man?” she whispered to the bat.

“Excuse me, Gert-RUDE!” said Mrs. Wintermacher. “Why are you talking to your pocket?”

“Sorry, just, um, asking the pocket how it likes being a pocket, I guess? Anyway, here I come! Make way, part the sea!” Gertrude gently squeezed her way to the front of the room, sweating in her white Taffetteen dress.

“Why does she have to be sooooo weird?” whispered Ellabelle Belle-Parker.

“Yeah, like, a certain amount of weird is cool—” said Posey Picard, “like how I randomly twirl my hair and say ‘money money money’—but she is beyond the legal limit.”

“I know,” whispered Imogen Crant. “She’s such a MILLICENT QUIBB!”

A hush fell over the room.

“Girls!” Mrs. Wintermacher bellowed. “We do not say that name! There are no mad scientists in this town, but if there were, they would be evil, but there aren’t, so shut up!”

The adults did seem to say this all the time, and their rabid insistence gave the impression that perhaps there actually WERE mad scientists in the town, or at least there used to be—and indeed, if you listened hard enough, you could hear whispered hushes about the one mad scientist that was said to remain, a certain Millicent Quibb, who, according to the popular hopscotch rhyme, had a habit of pickling brains.

But that was all faraway nonsense, and though the girls at Mrs. Wintermacher’s maintained a foggy awareness of its supposed origins, for them the phrase “Millicent Quibb” had simply come to mean “n. someone weird and bad, probably smelly.”

Gertrude was used to being called a Millicent Quibb, among other things, like Slug Lover (which was true; she loved slugs), Mayor Lover (also true; she was a great admirer of Mayor Majestina DeWeen, but who wasn’t?), and Most Likely to Sweat Through Taffetteen (definitely true). In fact, “a Millicent Quibb” was one of the nicest things Imogen Crant had ever called her, so Gertrude took it as a win and continued journeying toward the front of the room.

This journey was usually accompanied by a sense of dread, but today, Gertrude was actually excited to demonstrate, for today, Gertrude had…a plan!

She had come up with a rather ingenious way to sit with a perfectly straight spine. Finally, she would do something right at school, and she would make her little sisters proud, and she would make her cousins like her, and she would show Mrs. Wintermacher that she could be good at etiquette and could one day be a good citizen, helping the people and animals of Antiquarium just like Mayor Majestina DeWeen! Today was the day!

“Phew,” Gertrude said, having finally arrived at the front of the room. “That was a long journey. I should have taken a camel up here!”

“Enough, Miss Porch. Humor is for the ugly. Now, please demonstrate the ‘Upright Sit with Straight Back.’ This is the simplest of the fainting couch postures, ladies. If you can’t master this, there’s no hope.”

Gertrude planted her feet on the ground, sucked in her stomach, pinned back her shoulders, and waited for the verdict.

Mrs. Wintermacher held an architect’s protractor to her back to determine the angle of her spine.

“Ah,” she said, surveying the protractor. “Out of a possible ninety degrees, Miss Porch has managed…thirty-nine. Despite her best efforts, her posture still resembles that of a dead fern.”

The Lavinias snickered in unison.

Gertrude shrugged and laughed with them, which she was very good at doing, though she couldn’t help but notice that the inside of her chest felt like a bunch of dead ferns.

Eugenia and Dee-Dee didn’t know what to do to help their sister, so they started clapping—which did in fact make it worse. 2

But Gertrude pressed on. Fear not, Gertie, old chap! she thought. For today, you have a plan!

Gertrude faced her classmates. “Gosh,” she said. “My darn spine. Bent again. What ever will I do? Oh, I know!”

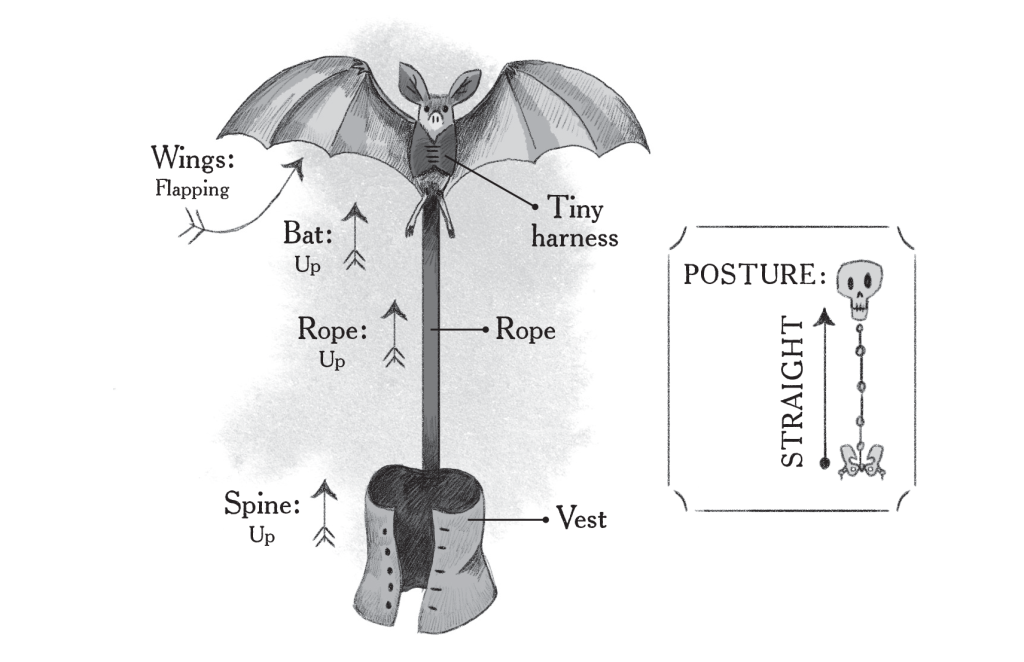

Gertrude pulled a vest from her left pocket, onto which she had sewn a rope with a tiny harness attached to the other end. From her right pocket she pulled a small brown bat, which she clipped into the tiny harness.

“Behold…the Bat Straightener!”

Gertrude donned the vest, then let the bat loose. The creature flew insistently toward the ceiling, tugging on the vest and instantly improving her posture. “Ta-da! A straight spine in no time!”

The reaction in the classroom was not what Gertrude had anticipated.

Her classmates jumped back in disgust.

“Euch! The devil!” Mrs. Wintermacher screamed. She disappeared behind a heavy velvet curtain, then reemerged moments later brandishing a rusted medieval javelin and rushed toward the bat, poised to kill.

Horrified, Gertrude released the bat from its harness, hoping it would fly away through an open window, but instead it flapped frantically around the room.

The girls screamed and scattered. Some huddled under chenille chaises, while others attempted to pelt the bat with tiny throw pillows.

Meanwhile, Eugenia shook her head as she watched Mrs. Wintermacher zigzag around the room, waving her javelin.

“Oh, grow up, it’s just a bat!” Eugenia pulled a heavy velvet curtain from a nearby window, then dragged it across the room and hurled it over Mrs. Wintermacher, tackling her to the ground.

As they fell, Eugenia and Mrs. Wintermacher knocked over a porcelain shepherdess, a vase of peonies, several Lavinias, and a lit candelabra.

“Wow. I suppose velvet really IS a cruel mistress,” said Eugenia.

The flame from the candelabra spread—first up a curtain, then down a rope, then across a settee, then down a doily, then across a rug, then up another velvet curtain, then across the ceiling, and finally onto a wooden chandelier, which came crashing down in a torrent of fire.

Dee-Dee sat quietly on the floor amidst the chaos and chewed on her toothpick, waiting for instructions. Lately she had found that if she sat with her ears open, she could hear helpful whispers from the objects around her. She heard a whisper from above, where a water pipe ran along the length of the ceiling. “Break me,” it said. She gave the water pipe a thumbs-up, then looked down at her miniature catapult and smiled. “I see,” she said to the catapult. “You have revealed your destiny.”

Dee-Dee launched the rock that Eugenia had been chipping at and it struck the pipe, forming a hairline fracture in the iron tube. Just a few drops of water trickled from the pipe at first, then the whole thing cracked open and a biblical flood rained down, dousing the flames.

All was still, save for the rushing of rain and the fluttering of bat wings as the creature escaped through the window.

Mrs. Wintermacher punched her way out of the pile of wet velvet, smoothed what was left of her eyebrows, plucked a single singed feather from her hat, and said:

“May I see the Porches in my office, please?”

“You three are officially expelled!” cried Mrs. Wintermacher.

“Ugh, fine by me!” Eugenia said. “This school is a factory of insidious conformism!”

Gertrude felt again that her chest was full of dead ferns, and that the dead ferns were now on fire. Still, she managed to raise her finger politely. “Um, Mrs. Wintermacher, the thing is, we kind of already got kicked out of the eight other etiquette schools in town, and I think our mother and father, well, our fake aunt and fake uncle, I mean, our semi-permanent adoptive mother-aunt and father-uncle, well, I think when they hear this news they might kick us out of the house—”

“That’s none of my concern,” said Mrs. Wintermacher. “You must face the music.”

“If you tell us what direction the music is coming from,” said Dee-Dee, “then surely we can face it.”

“It is a metaphor, you imbecile!”

Unbothered, Dee-Dee turned her head toward the southwest corner of the room. “Ah yes, I think I hear the music now. It’s lovely, thank you.”

“Gahh!” Mrs. Wintermacher said. “Enough! I pray that I never have to see your horrible faces again, even on a wanted poster! Now, run away before I find my javelin!”

And so the Porches sprinted to the backpack room and collected their backpacks, never to return—or so they thought.

Hot white sun baked the sidewalk outside Mrs. Wintermacher’s school as the Porches trudged home.

Gertrude felt as if her guts had fallen out of her body and were being eaten slowly by pigeons and beetles. Her spine drooped even lower than thirty-nine degrees. It was all her fault.

“I’m…sorry I got us kicked out, guys. I thought the Bat Straightener was a good idea.”

“This town wouldn’t know a good idea if it bit it in the eyeball,” Eugenia said. “We are drowning in an intellectual and moral cesspool.”

“Ah, the cesspool. The humblest of pools,” Dee-Dee sighed wistfully.

“I hope I can make it up to you someday,” Gertrude said.

“If you can’t make me thirty-six years old with a luxury apartment in Paris, then you can’t do a thing for me,” said Eugenia.

“I’d like some doll clothes,” said Dee-Dee. “In case I ever shrink.”

Though her sisters were being kind, Gertrude still felt rotten.

She wanted, more than anything, to be good, or at the very least, good enough; to be a beloved family member, an esteemed community member, a protector to all living creatures, no matter how helpless or reviled. But what it meant to be good enough in Antiquarium had very little overlap with the skills and qualities she naturally had on offer. What to do when you can’t change the world, and you can’t change yourself? One does grow weary, shimmying endlessly between a rock and a hard place.

Never again, Gert! she thought. From now on, keep your head down and don’t do anything weird. You have to take care of your sisters, who are good and who deserve to have good and easy lives.…Darn, there are those tears again. I wonder what makes tears? Is it fluid from the brain? Is there a separate tear reservoir? Maybe it’s in the chin, and that’s why the chin trembles when it’s time to cry?

She reached into her backpack for an old rag to wipe her face, and that’s where she found it:

…the thing that would start their journey…

…the thing that would keep them up at night, forever…

…the thing that would ruin their lives, or save them, or wasn’t it sometimes both…

- I tell you this because your journey to become a young mad scientist will probably begin with a mysterious invitation. Of course it could also begin with you finding a mysterious book of laboratory notes, a mysterious bag of medical instruments, or a mysterious store of stuff in jars. In the 1950s it was common to be snatched into a car by the FBI; in the ’90s, chain e-mail. But paper invitations are making a comeback—which is good, because they bring a greater sense of fun—so you should be prepared. ↩︎

- Have you ever heard the sound of only two people clapping? It is somehow much worse than the sound of zero people clapping. ↩︎

PREORDER YOUR COPY!

From beloved Saturday Night Live alum Kate McKinnon comes a madcap new adventure about three sisters, a ravenous worm, and a mysterious mad scientist!

So, you want to be a young mad scientist. Congratulations! Admitting it is the first step. The second step is reading the (definitely true) tale of the Porch sisters…

Gertrude, Eugenia, and Dee-Dee Porch do not belong. They don’t belong in the snooty town of Antiquarium, where all girls have to go to etiquette school and the only dog allowed is the bichon frise. They don’t belong with their adoptive family, where all their cousins are named Lavinia and their Aunt has more brooches than books. And they certainly don’t belong at Mrs. Wintermacher’s etiquette school—they’re far more interested in science. After getting kicked out of the last etiquette school that would take them, the girls expect to be sent away for good… until they receive a mysterious invitation to new school.

Suddenly the girls are under the tutelage of the infamous Millicent Quibb—a mad scientist with worms in her hair and oysters in her bathtub. At 231 Mysterium Way, the pizza is fatal, the bus is powered by Gerbils, and the Dean of Students is a hermit crab. Dangerous? Yes! More fun than they’ve ever had? Absolutely! But when the sisters are asked to save their town from an evil cabal of nefarious mad scientists, they must learn to embrace what has always made them stand out, and determine what side they’re on—before it’s too late!