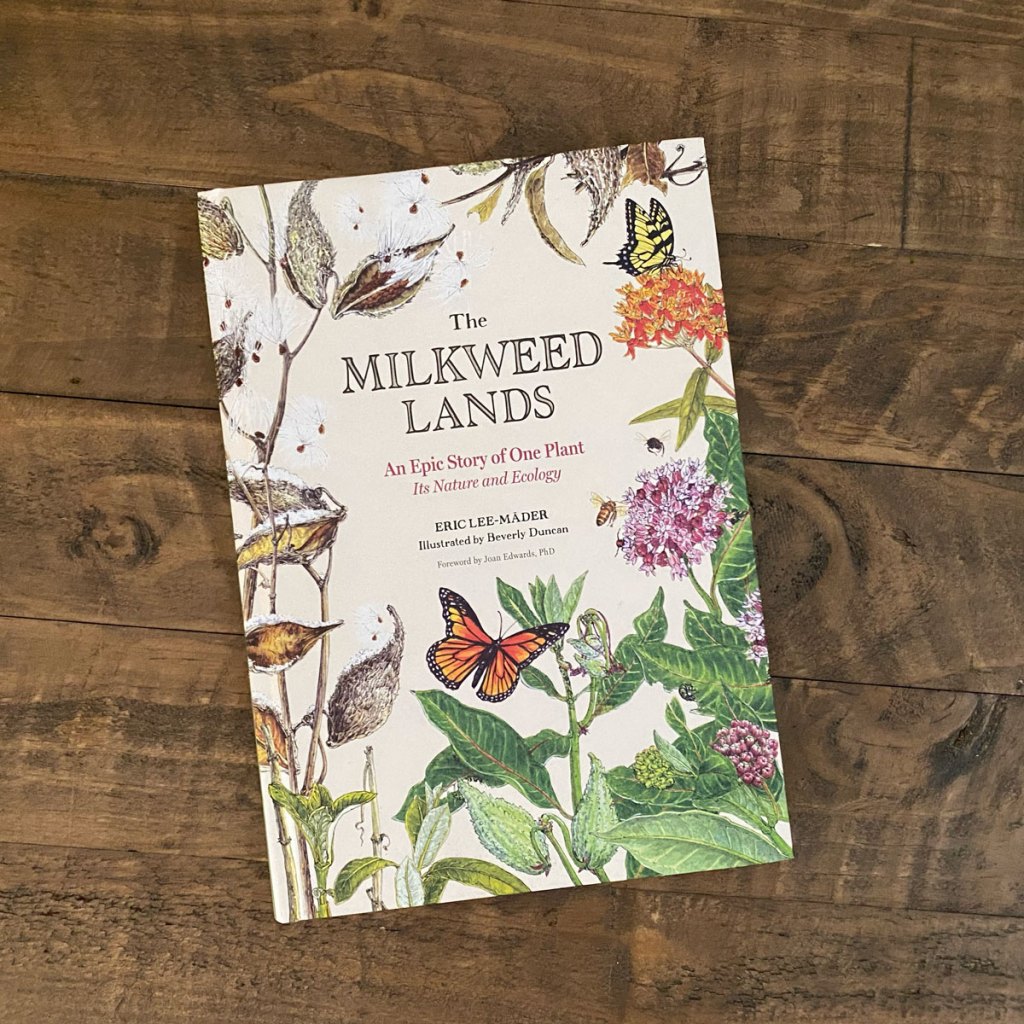

The Intricate Dance of Milkweed Pollination

Discover the fascinating world of milkweed flowers and their unique relationship with pollinators, as featured in The Milkweed Lands.

A Most Intricate Flower

Flowers are the pinnacle of summer for milkweeds, and, true to character, milkweed makes flowers that diverge into their own extraordinary brand of weirdness.

Among the plant kingdom, flower structures range from simple to complex. Most of us recall this from grade school biology, the simplified illustrations of tuliplike flowers with their stamens and styles, the male and female sex organs, respectively. Depending on the species, these may be combined with an elaborate perianth of colorful petals or large sepals. A flower may or may not produce nectar. A plant may have separate male and female flowers or ones that contain both sex organs. Flowers may grow singly or in complex compound arrangements. All of this is fairly fundamental botany and easy enough to grasp.

Milkweed flowers exist on a different plane. Despite their pedigree as ditch weeds, muck plants, or odd botanical outcasts of harsh and dismal places, even the most commonplace milkweed flowers have a complexity comparable to that of rare orchids. They are among the most elaborate flowers in the plant kingdom.

Pollinator Entanglements

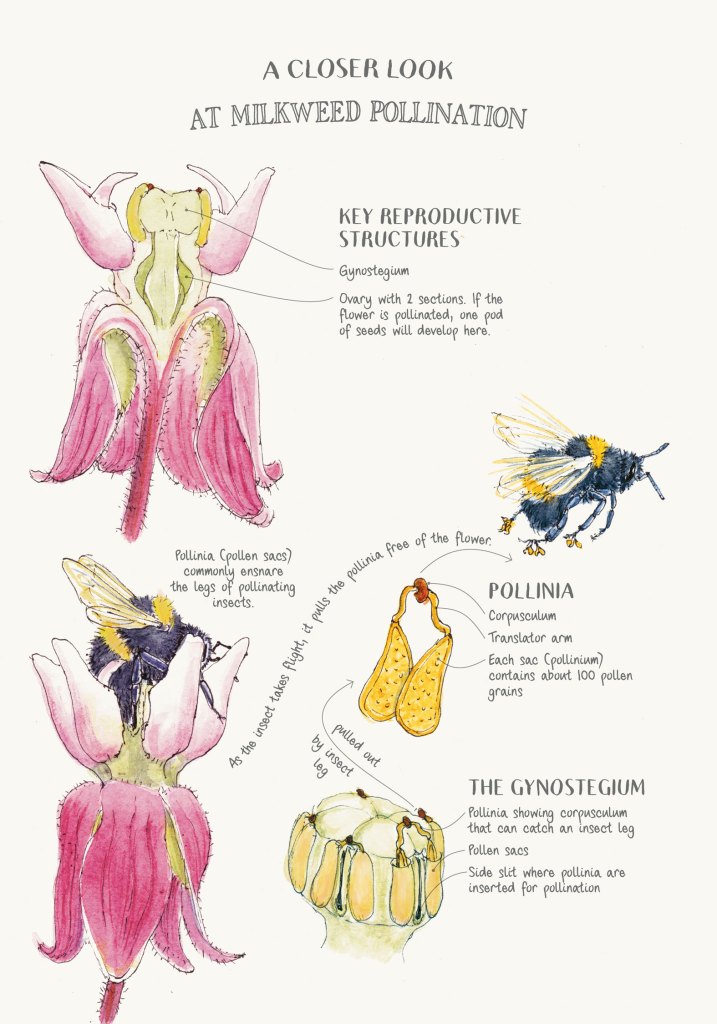

Among the notable features of milkweed flowers are the pollinia (singular: pollinium). These sacs of waxy pollen arise in a ring around the base of the gynostegium. Few other plant groups deliver their pollen this way—orchids being an exception. Most other flowering plants produce individually dispersed grains of pollen.

Milkweed pollinia occur in pairs, joined by a sort of wishbone configuration of filaments called translators and a structure called a corpusculum. This acts as a trip wire or trap, attaching itself to the legs or tongues of insects that probe milkweed flowers for nectar.

Bees and wasps, which tend to have numerous small, complex leg spines and claws, are the most frequent bearers of this burden. Small bees can be trapped by the corpusculum and die while stuck to a flower, unable to pull themselves free. Other bees or wasps that make repeated trips to milkweed flowers can have numerous pollinia attached to their feet, making walking cumbersome. Bumble bees can end up with pollinia affixed like binder clips to their tongues.

As an insect travels among flowers, the translator arms of pollinia dry and change shape, causing the sacs to flex outward. This slight shape change creates a sort of key that conveniently and perfectly fits into a milkweed flower’s stigmatic slits, located concentrically around the sides of the gynostegium, directly between the slots that produce pollinia.

The insect lands on a new milkweed flower and rotates the pollinia 90 degrees. The key slips into a lock, the insect is relieved of its burden—and a milkweed flower is pollinated.

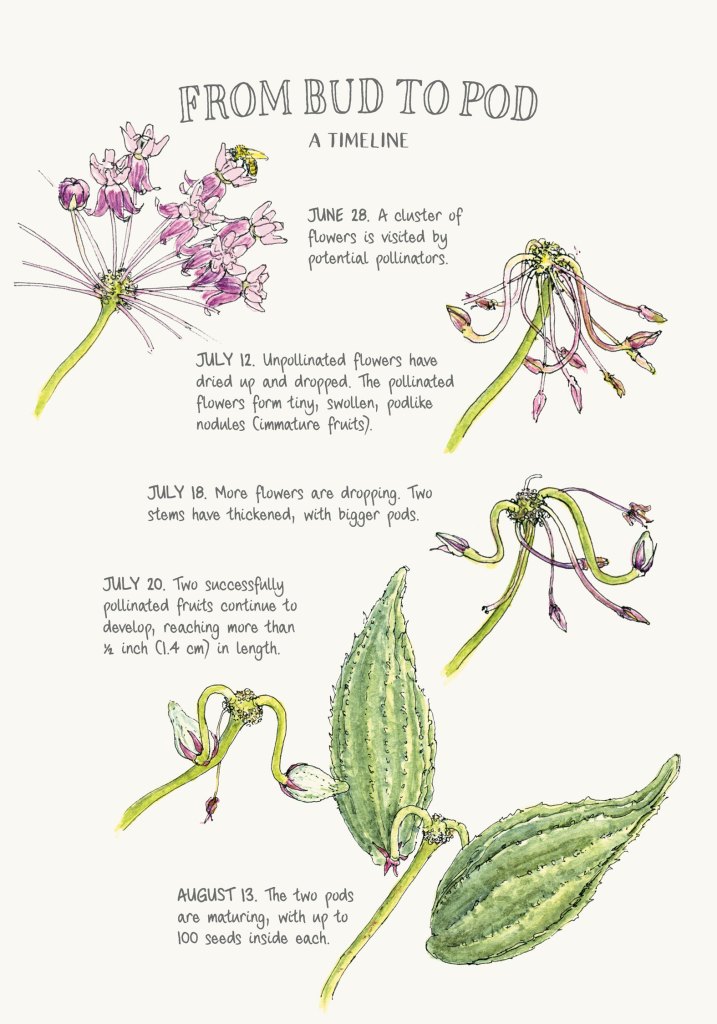

A fruit, or follicle (the pod packed with seeds), is the end result of a single delicate removal and replacement of pollinia between two milkweed plants.

The odds of all of this happening just so are seemingly astronomical, although the configuration of the flower, including the horn structures, helps guide the footwork of insects so that pollination will succeed. Moreover, since pollinia take some time to change their shape before fitting into a stigmatic slit, an insect has time to fly around and find an unrelated plant to cross-pollinate.

Still, we know that milkweed pollination is tricky enough business that many flowers seemingly go unpollinated and never make seed. Examining the marvelous pom-pom flower heads of common milkweed, which can contain many dozens of individual flowers, we discover that it’s common for only a single one in the cluster to actually be pollinated.

On the other hand, because a single pollinium sac may contain a hundred pollen grains, and a single milkweed flower’s ovary may contain a similar number of ovules, the difficult business of milkweed pollination needs to happen only a few times for a plant to create a tremendous number of seeds.

Milkweeds seem to be variable in how much they need cross-pollination between unrelated individuals. Some are thought to have a high degree of self-incompatibility, refusing to be pollinated by their own pollinia. Others seem a little more tolerant of this. In either case, where milkweeds are lost to mowing, herbicides, and habitat fragmentation, the pollination linkages may break down.

Excerpted and adapted from The Milkweed Lands © Eric Lee-Mäder.

National Outdoor Book Award Winner

Delve into this fascinating appreciation of milkweed, an often-overlooked plant, and discover an amazing range of insects and organisms that depend on it as the seasons unfold, with this collaboration between a noted ecologist and an award-winning botanical illustrator.