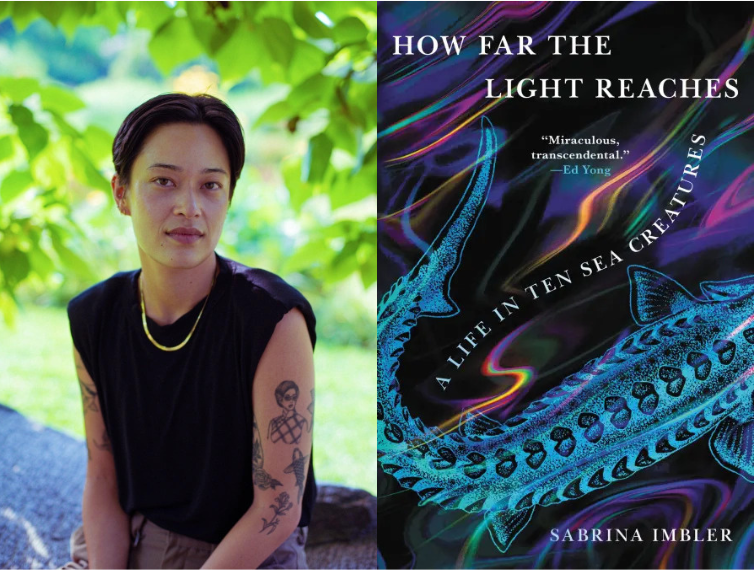

Sabrina Imbler

Sabrina Imbler (they/them) is a writer and science journalist living in Brooklyn. Their first chapbook, Dyke (geology) was published by Black Lawrence Press. They have received fellowships and scholarships from the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Tin House, the Jack Jones Literary Arts Retreat, Millay Arts, and Paragraph NY, and their work has been supported by the Café Royal Cultural Foundation. Their essays and reporting have appeared in various publications, including the New York Times, the Atlantic, Catapult, and Sierra, among others.

A queer, mixed race writer working in a largely white, male field, science and conservation journalist Sabrina Imbler has always been drawn to the mystery of life in the sea, and particularly to creatures living in hostile or remote environments. Each essay in their debut collection profiles one such creature. Imbler discovers that some of the most radical models of family, community, and care can be found in the sea. Exploring themes of adaptation, survival, sexuality, and care, and weaving the wonders of marine biology with stories of their own family, relationships, and coming of age, How Far the Light Reaches is a book that invites us to envision wilder, grander, and more abundant possibilities for the way we live.

The summer after I graduated college, I moved to New York to intern at a magazine that paid me $10 an hour, so I also freelanced for an ocean nonprofit. I would scour Google News every week to find weird or surprising news about the ocean, which helped introduce me to many of the creatures in this book. But there was one headline in Reuters that I never forgot: “Octopus mom protects her eggs for an astonishing 4-1/2 years.” I read through the story, which described a deep-sea octopus at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean that guarded her eggs for four-and-a-half years without moving or eating anything. I was stunned, and I couldn’t stop thinking about her. I knew octopuses have an incredible, bodily intelligence that extends beyond the reaches of what our human brains can imagine. I knew octopuses could escape their tanks and unlock jars and hide themselves in coconuts. What was it like for such an animal to sit, unmoving and wasting away, for so many years?

The octopus had implanted herself into my mind, and I knew I wanted to write about her but wasn’t sure how. A few years later, I saw the online magazine called Catapult had opened submissions for columns. I pitched a column inspired by the octopus, where I would mix memoir and science writing to see what lessons I could draw from the ways sea creatures survive in the ocean. The first essay was about the mother octopus and my own mother, which I expanded for the book. All the creatures in the book have carved out space in my heart, the mother octopus is at its beating center, the creature whose life felt refracted from my own.

Gay “Blue Planet”

Like many other gay people, I grew up worshipping at the altar of Tamora Pierce. I dreamed of living in the young-adult kingdom of Tortall. All of Pierce’s young protagonists were role models for me, gender-bending people who shed off societal expectations to become the person of their dreams. There’s Alanna, the young girl who disguises herself as a boy to become a knight. There’s Kel, the girl who becomes a knight as a girl (thanks to Alanna’s trailblazing.) But my favorite of Pierce’s series in Tortall is “The Immortals,” starring a girl named Daine, who can speak to animals, briefly lived with wolves after bandits murdered her family, regularly communes with The Badger God, and also raises a dragon before it was cool. Daine is my number one, and Pierce’s books were probably the reason I wanted to become a writer. I remember sometime when I was in elementary, Tamora came to my local bookstore to sign some books and I brought my heavily dog-eared copies in a sizeable stack, and she was kind enough to sign every single one.

Writing this book for years on top of a day job where I also write about science made it hard to imagine ever writing another book—what on earth do I have left to say about the ocean?! But when I was doing my final edits of the book, not writing very much but cutting a lot, I found myself watching Joe Wright’s 2005 film Pride and Prejudice, which stars Keira Knightley looking impish in fields and kitchens and various balls and Matthew Macfadyen looking surly in all the same places and occasionally clenching his surly little fist. It’s become a comfort movie for me, one I watch to be swaddled in vibes and ambience and muted period horniness. I became propelled by the urge to write something fun and campy and gay in that same period. So I started writing historical fanfiction about the spurned ex of a Regency-era lesbian who has gotten a surprising amount of public attention, considering she died more than 140 years ago. It’s my attempt at a Jane Austen-era romantic comedy in a world where there are queer and trans people. Who knows if it will go anywhere, but for now it has been giving me a lot of joy!

Not to be a Daine, but I wish I could communicate with animals. Specifically my cats, Sesame and Melon. I want to know what they think about when I am home, when I am gone. I want to know if they dream. I want to know what they think of each other! I want them to know that I will love them forever! Melon is still a baby, and I love to watch her experience the world. New things amaze her—the taste of yogurt, an earthworm, a gust of wind. I want to know what she thinks of all this wonder.