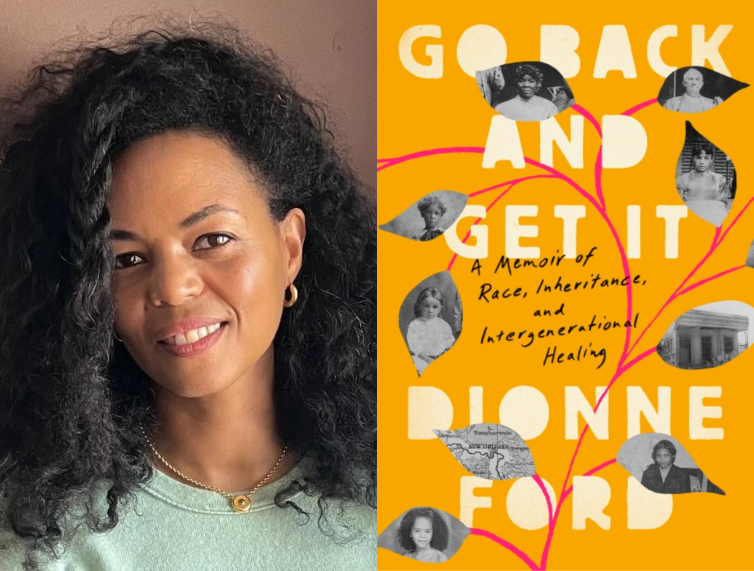

Dionne Ford

Dionne Ford (she/her) is an NEA creative writing fellow and the co-editor of the anthology Slavery’s Descendants: Shared Legacies of Race and Reconciliation (Rutgers University Press). Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Literary Hub, New Jersey Monthly, the Rumpus, and Ebony and won awards from the National Association of Black Journalists and the Newswomen’s Club of New York. She holds a BA from Fordham University and an MFA from New York University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and daughters.

An unexpected family photograph leads Dionne Ford to uncover the stories of her enslaved female ancestors, reclaim their power, and begin to heal.

To heal, Ford tries a wide range of therapies, lifestyle changes, and recovery meetings. “Anything,” she writes, “to keep from going back there.” But what she learns is that she needs to go back there, to return to her female ancestors, and unearth what she can about them to start to feel whole.

Stories are medicine.

The podcasts The Slowdown and GirlTrek, and a personal playlist that starts with Solange’s Dream and ends with Gilberto Gil’s “Lamento Sertanejo”.

My daughter Devany is a great cook and the paella she made for us during our pandemic New Years Eve was amazing.

On Insta @beverlymahone aka “Auntie Bev” because who doesn’t want to improve their vocabulary? On Twitter @MauriceRuffin because he always shares positive wisdom for writing and living.

The Bible because it was always available and didn’t need to be read in order, The Peanuts comic books, and Judy Blume’s Are You there God? It’s Me Margaret.

Loyal, sensual, down-to-earth and tenacious, I am a typical Taurus, but I refuse to believe the stubborn part.

Countless Black Americans descended from slavery are related to the enslavers who bought and sold their ancestors. Among them is Dionne Ford, whose great grandmother was the last of six children born to a Louisiana cotton broker and the enslaved woman he received as a wedding gift.

What shapes does this kind of intergenerational trauma take? In these pages, which move between her inner life and deep research, Ford tells us. It manifests as alcoholism and post-traumatic stress; it finds echoes in her own experience of sexual abuse at the hands of a relative, and in the ways in which she builds her own interracial family.

To heal, Ford tries a wide range of therapies, lifestyle changes, and recovery meetings. “Anything,” she writes, “to keep from going back there.” But what she learns is that she needs to go back there, to return to her female ancestors, and unearth what she can about them to start to feel whole.