Excerpt from MAKE IT COUNT

Our coach has good news. He’s going to tell us after practice. First, we train.

I’ve been competing now for about two years. Getting stronger, getting faster. I’m in sixth grade, at Calabar Infant, Primary, and Junior High School in Kingston. I’m on the relay team. Our event is the 4 x 100 meters. We don’t have a track at school, so we run drills in the parking lot of the East Queen St. Baptist Church, in the shade of the large redbrick building. Today, we’re practicing our handoffs. I start the race, sprint my hundred meters, then hand the baton to the second person, who hands it off to the third, who hands it off to the fourth. He’s the anchor. The fastest boy on the team. I’m the fastest of them all, but I’m not a boy.

I’m a girl who runs with the boys. I never say this out loud, but that’s how I feel. I spend each practice grappling with the sensation of being out of place. Out of my body. I’m on the wrong team. But even still, I love running. This is something I’m good at. Something I love. It feels worth it—to hide who I am, in order to do something that brings me such joy. And there are some advantages to being a girl who trains with boys. The boys push me to be faster, stronger. They’re good teammates. Supportive. When I’m training, I don’t get the hate and harassment that I’ve become accustomed to in Jamaica while walking the streets. I don’t get called battyman, I don’t get threatened, I don’t fear for my life. On the field, I’m respected. On the field, I’m an athlete. That magic word. My protection. It’s a part of my identity now. My teammates admire me for my abilities, my friends stand up for me no matter what. I feel more confident in who I am.

We finish our practice. The coach tells us to gather around. He says our times today were good, but they can be better. And we’re going to work to make them better.

Because our relay team has qualified for the National Championships.

My mom will miss the meet.

She’s gone again, back to Canada to work. It’s just me and Terrence at the house. He says he’s happy for me, proud that I made it all the way to the national competition. But he can’t come either. He has something to do that day. He doesn’t tell me what it is. I don’t ask. I think I know what he gets up to when my mom isn’t around. I think he sees other women.

So, I’ll go alone.

The day comes. The event is officially called Inter-Secondary Schools Boys and Girls Championships, but everyone just calls it Champs. The track team meets up at the school, where buses are waiting to take us to the meet. We load in, laughing and chatting and yelling. There’s a nervous energy; the anticipation is like an electric current, buzzing through our bodies on the bus. We speed toward our destination.

Then, it appears: National Stadium. We crane our necks to take it in as we pull into the parking lot. It towers above us. A series of white concrete arches curve over the entrance, coming to points in the sky. Crowds of people file in, looking so small in the shadow of the stadium.

The bus comes to a stop. The doors open. Our coach leads the way to the entrance. We pass a bronze statue of Bob Marley, hold- ing his guitar. We join the crush of bodies funneling their way into the stadium. I know that this is where some of the greatest Olym- pians in the world have competed. And now, I get to compete here too. I can feel the heat from the crowd, the excitement. But nothing matches the thrill I feel when I walk onto the field. It stretches on for what feels like forever. Our coach says the stadium can hold up to 35,000 people. The bright blue track encircles a vibrant green field. This is nothing like the dirt tracks we run on at school. I look up into the stands, imagine all the roaring crowds that have witnessed historic wins.

Spectators file into their seats, waving at my teammates. It seems like everyone else on my team has a group of loved ones there to sup- port them; parents and aunts and uncles and cousins and friends fill the bleachers, shouting words of encouragement, holding up hand- made signs.

But no one is here for me. Terrence is busy. Auntie Peaches is consumed, as she usually is these days, by the grind of being a single mother to young children, too busy with work to make a weekday meet.

I think of my mother. Wonder what she’s doing in Canada. Is she thinking of me? I wish she was here. I want her to join all the other cheering family members in the stands. I want her to share this moment with me. I want to make her proud. I’ve made it here, to Champs. And I got here doing something I love, something I’m good at, something that other people find impressive. Why does it seem like she doesn’t understand that? I feel so lonely. But I also feel more determined than ever to succeed. Maybe if I keep winning, maybe if I keep gaining a bigger and bigger reputation as an ath- lete, maybe if I work harder than I’ve ever worked before, maybe if I make it to the Olympics, maybe if I achieve something so remarkable, so huge, so undeniable, then my mother will finally support me in the way I wish she would.

Because sometimes I feel like there’s a hole in my heart in the shape of my mother.

But I can’t get distracted with these thoughts.

I have to focus on the competition. I am learning that to perform to the best of my ability, I have to clear my mind before hitting the track. I have to drown out the noise of the world. I have to focus on the task at hand and nothing else.

The time comes for our event. I’m the first sprinter in our relay. I go to my starting block, watch the rest of our team get into position. Our competitors go to their own lanes, preparing for the race. Silence falls over the field. Isolated cheers erupt from the stands. A stillness overwhelms me, a feeling of serenity, the feeling that I’m in the right place. This is what I was born to do. I’m at home here, on this track, the same track that’s weathered the footsteps of so many world-class athletes before me.

I could be one of them. At some point in my life, somewhere down the line, I could be an Olympian. A dream begins to form in the back of my mind. A dream that one day this sport that I love will take me to glory. Not just for myself, but for my teammates, my family, and everyone I love.

But then, another thought enters my mind. A realization: They will want me to compete with the boys. Like I am now. If I ever make it to Team Jamaica, there’s no way they will ever let me run with the females. And I know this because I know what it’s like for me to live in Jamaica, I know how it feels to be bullied, to be called a battyman, to have people taunt you because they say you walk like a girl, talk like a girl. I know that Team Jamaica will never honor who I am and will never see my true self. I will have to lie about who I am to compete on the world stage. And that’s just something I don’t want to do. It’s already painful enough to have to hide who I am today, on this field, with everyone watching, thinking that I’m just another one of the boys, even though I’m not. I’m a girl.

On your marks!

But I love this sport. Love it more than anything else in my life.

Get set.

Except for my sister. And my mother.

Boom! The gun goes off. I’m out of the blocks. Bolting down the lane. The baton is tight in my grip. It’s just me and the track and my teammates. Adrenaline pumps through my system. All my thoughts dissipate, all my anxieties vanish. The only thing that matters at that moment: the finish line.

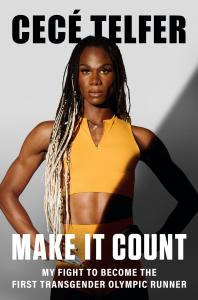

This “moving, deeply human” memoir tells the inspiring story of the first openly transgender woman to win a NCAA title, following the obstacles she overcame to achieve her Olympic dreams (The Cut).

CeCé Telfer is a warrior. She has contended with transphobia on and off the track since childhood. Now, she stands at the crossroads of a national and international conversation about equity in sports, forced to advocate for her personhood and rights at every turn. After spending years training for the 2024 Olympics, Telfer has been sidelined and silenced more times than she can count. But she’s never been good at taking no for an answer.

Make It Count is Telfer’s raw and inspiring story. From coming of age in Jamaica, where she grew up hearing a constant barrage of slurs, to living in the backseat of her car while searching for a coach, to Mexico, where she trained for the US Trials, this book follows the arc of Telfer’s Olympic dream. This is the story of running on what feels like the edge of a knife, of what it means to compete when you’re treated not just as an athlete, but as a walking controversy. But it’s also the story of resilience and athleticism, of a runner who found a clarity in her sport that otherwise eluded her—a sense of simply being alive, a human moving through space—finally, herself.