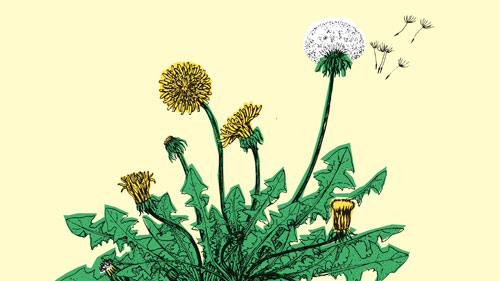

8 Native Plants for Native Medicine

Many of the plant medicines widely available in pharmacies and health food stores are the same powerful healers they have been for centuries.

While many of us are familiar with botanical immune boosters like echinacea and elderberry, or the skin-soothing power of witch hazel (to name just a few), there are countless other plants native to North America that have deep medicinal roots. Since ancient times people have needed plants not only for their very survival but also to enrich their lives and make the act of living a bit more comfortable.

Here are eight potent plants whose traditional uses by the ancestors of this continent’s indigenous people continues to inform and shape how we treat our ailments and support human health.

California Poppy

All parts of the California poppy plant — from its bright orange roots to its leaves, flowers, and seedpods — can be used medicinally. Members of the Costanoan tribe prepared the flowers as a strong tea to rinse their hair, to kill head lice. The Ohlone people crushed the seeds and mixed them with bear fat as a hair tonic dressing. Tribes in the Mendocino area juiced the roots to treat many different ailments, from headaches to stomachaches to toothaches, and nursing mothers would wash their breasts with the root juice to help dry the flow of milk when it was time to wean their babies; Pomo women made a poultice or a strong tea from the mashed seedpods and applied it to their breasts for the same purpose.

Gooseberry & Currants

Indigenous people in North America have long used currants and gooseberries medicinally. The Comanche people used a berry tea as a gargle to soothe inflamed throats. The Prairie Potawatomi tribe made a decoction from the root, which was a good eyewash to remove foreign particles or soothe tired or infected eyes. To expel intestinal worms, the Muscogee (Creek) tribe drank a strong tea made from the root bark. Gooseberry juice was also applied to the skin as a wash to soothe irritated and inflamed skin tissue.

Milkweed

A number of Native tribes have used the latex juice from the milkweed roots, plant tops, and stem for medicinal purposes. The Miwok people used the latex to remove warts. The Cheyenne made a decoction of the dried plant tops and used it as an eyewash to heal snow blindness. Cherokee, Delaware, and Mohegan peoples used pleurisy root, also called butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), made into a cough remedy.

Nettles

The Hesquiaht and the Miwok peoples used the plant to relieve muscle and joint pain — sometimes by whipping stems of fresh nettles over the affected body areas. The formic acid contacting the skin caused a temporary burning and blistering, but it also created a rush of circulation to those parts. This improved circulation in the muscles and joints gave some lasting pain relief for conditions like arthritis. Cherokee people prepared a tea from nettles and drank it as a stomach tonic. The Cree Indians considered nettles an important women’s herb during childbirth.

Persimmon

The Cherokee people picked the fruits just before first frost and made them into an astringent medicinal syrup to treat diarrhea. The Choctaw sun-dried the fruit and baked it into a bread for the same purpose. People of the Catawba tribe made a poultice of the fruit to remove warts and a decoction from the tree’s bark to use as a mouthwash for thrush (a type of fungal infection). The Rappahannock Indians chewed the bark to relieve heartburn.

Spruce

Native Americans knew tea brewed from spruce needles helped people stay healthy during long, cold winters. In the 1500s colonists in Quebec City began to suffer from scurvy (caused from a vitamin C deficiency). The Iroquois Indians shared this important remedy with them. Drinking spruce tea and spruce beer, called Newfoundland spruce beer, not only healed them of scurvy, it became an important preventive step.

Willow

The Choctaw and the Delaware Indians, along with many other tribes, used peachleaf willow (S. amygdaloides) and other species to fashion a toothbrush of sorts from a small willow twig. It would clean their teeth, and the astringency of the tannins helped to keep gums healthy.

Yew

Traditionally, women of the Okanagan tribe and other northwestern coastal tribes ate yew berries as a form of contraception. The Quinault people prepared the bark as a decoction and drank it in very small doses to relieve arthritis, tuberculosis, and kidney disease. The Cowlitz Indians made a poultice of the needles and applied it topically to wounds. The leaves are not taken internally, however, as they are poisonous.

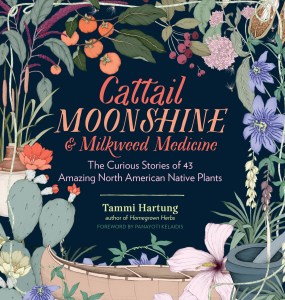

Text excerpted from Cattail Moonshine & Milkweed Medicine © Tammi Hartung. Illustrations © Edith Rewa Barrett.

2016 Silver Nautilus Book Award Winner

History, literature, and botany meet in this charming tour of how humans have relied on plants to nourish, shelter, heal, clothe, and even entertain us. Did you know that during World War II, the US Navy paid kids to collect milkweed’s fluffy white floss, which was then used as filling for life preservers? And Native Americans in the deserts of the Southwest traditionally crafted tattoo needles from prickly pear cactus spines. These are just two of the dozens of tidbits that Tammi Hartung highlights in the tales of 43 native North American flowers, herbs, and trees that have rescued and delighted us for centuries.